The Math Behind Prime Movers: The Decision Velocity Formula

Create more opportunities to win in the same 24 hours everyone else has.

Founder-Led Companies Outperform by 3.1x. The Advantage Lives in the Mechanism Nobody Named.

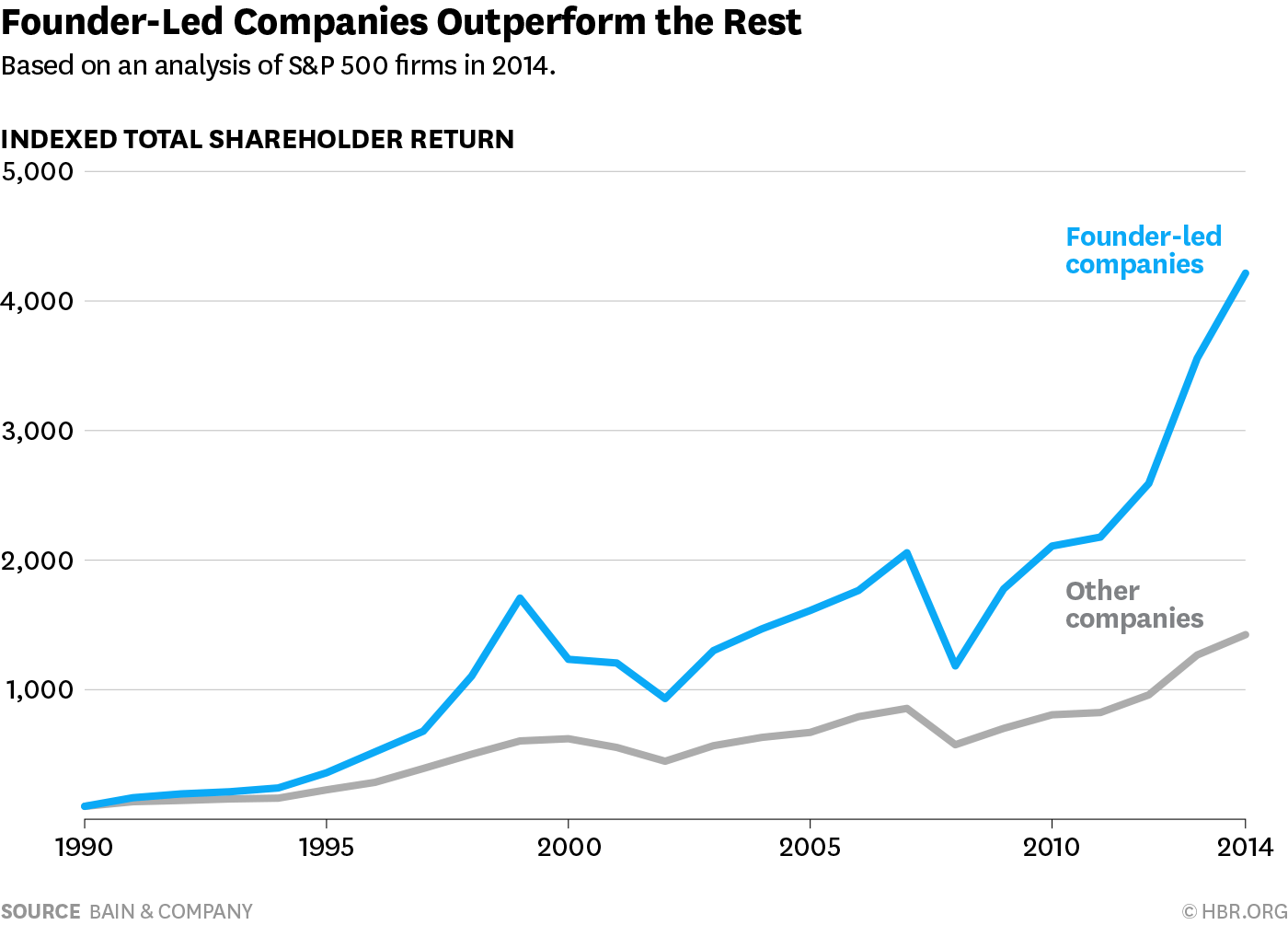

In 2016, Bain analyzed S&P 500 companies across a 24-year period and confirmed what operators had long suspected: founder-led companies materially outperform. From 1990 to 2014, these firms consistently delivered 3.1x higher returns than their peers.

Bain named three differentiators: Business Insurgency, Front-line Obsession, and Owner’s Mindset.

Good descriptions. Accurate observations. But here’s what they didn’t explain: the mechanism.

Why does Business Insurgency translate to better decisions?

How does Front-line Obsession create faster learning?

What specifically about Owner’s Mindset produces 3.1x returns?

The research named the effect. It didn’t reveal the cause.

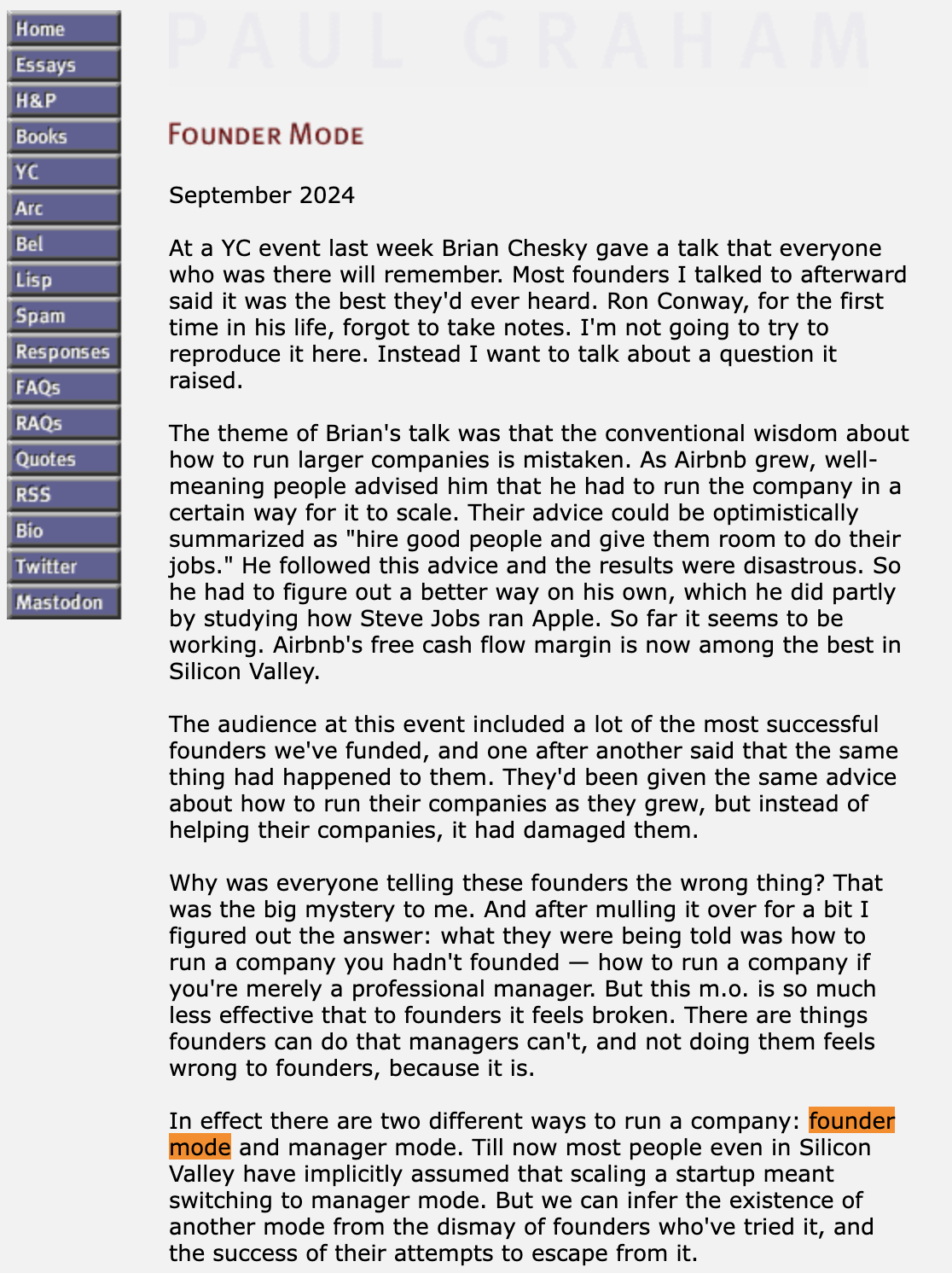

For eight years, people speculated. Then Paul Graham wrote an essay that went viral overnight—giving the phenomenon a name that still dominates every strategy conversation: Founder Mode.

The essay crystallized what operators had felt for years: there’s a way founders run companies that conventional management wisdom can’t explain. And it made it sound cool.

“He went into founder mode and changed the entire company.”

“Time to go into founder mode!”

The term became instant shorthand for something everyone recognized but nobody could quite define.

Graham’s admission was the most revealing part: “Business schools don’t know it exists, so they can’t teach it.”

Ten years of data. One viral essay. Zero mechanism.

Everyone agrees founder-led companies perform differently.

Almost nobody explains how.

The Bain research gave us the what—founders outperform. Graham’s essay gave us the name—Founder Mode. But neither answered the operational question that matters: What’s the mechanism that makes 3.1x possible?

The answer isn’t founder charisma, founder hustle, or founder intuition. It’s something more specific and—more importantly—something buildable: Decision Velocity.

Founders don’t just work differently. They decide differently. And the difference is measurable.

Here’s how.

What Everyone Sees—And What’s Actually Happening

Watch a founder-led company operate and certain patterns emerge.

They iterate faster. They course-correct before small problems become expensive ones. They run more experiments in a quarter than competitors run in a year. When market conditions shift, they’ve already adjusted—sometimes before the shift is obvious to everyone else.

From the outside, it looks like superhuman sprint capability. Like they’re playing the game at 3x speed while everyone else moves at normal tempo.

The surface explanations write themselves: Founders work harder. Founders care more. Founders have more at stake.

These explanations feel true. They’re also incomplete.

Plenty of professional managers work brutal hours. Plenty of hired CEOs genuinely care about outcomes. Plenty of leadership teams have significant equity stakes. Yet the performance gap persists.

Working harder doesn’t explain faster iteration. Caring more doesn’t explain better course corrections. Having stake doesn’t explain more experiments.

Something else is happening. Something the “work harder, care more” narrative misses entirely.

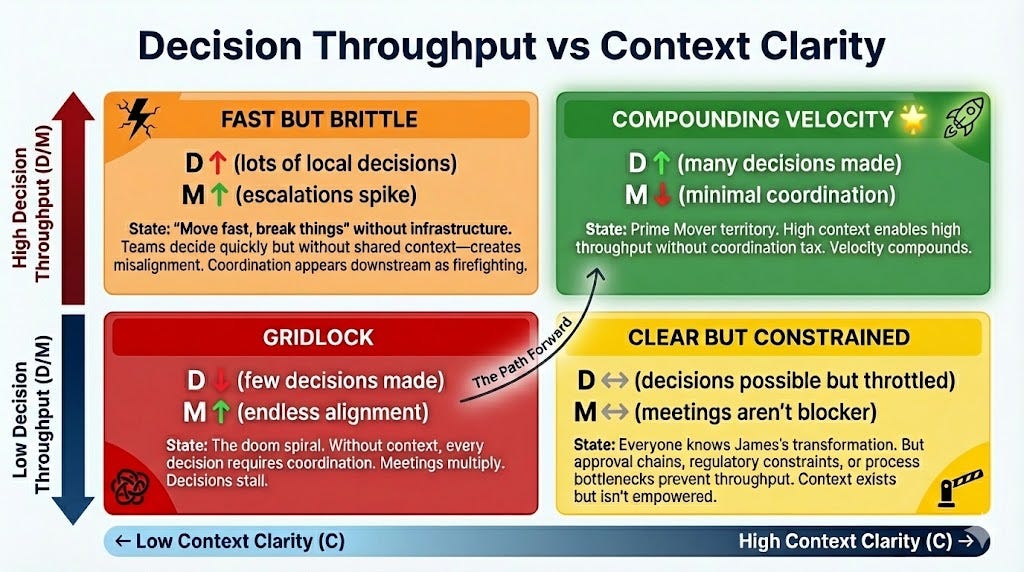

The difference isn’t effort or motivation. It’s how many quality decisions get made per unit of time.

This is what creates Prime Movers—individuals whose decision patterns predict category ownership.

And it’s measurable:

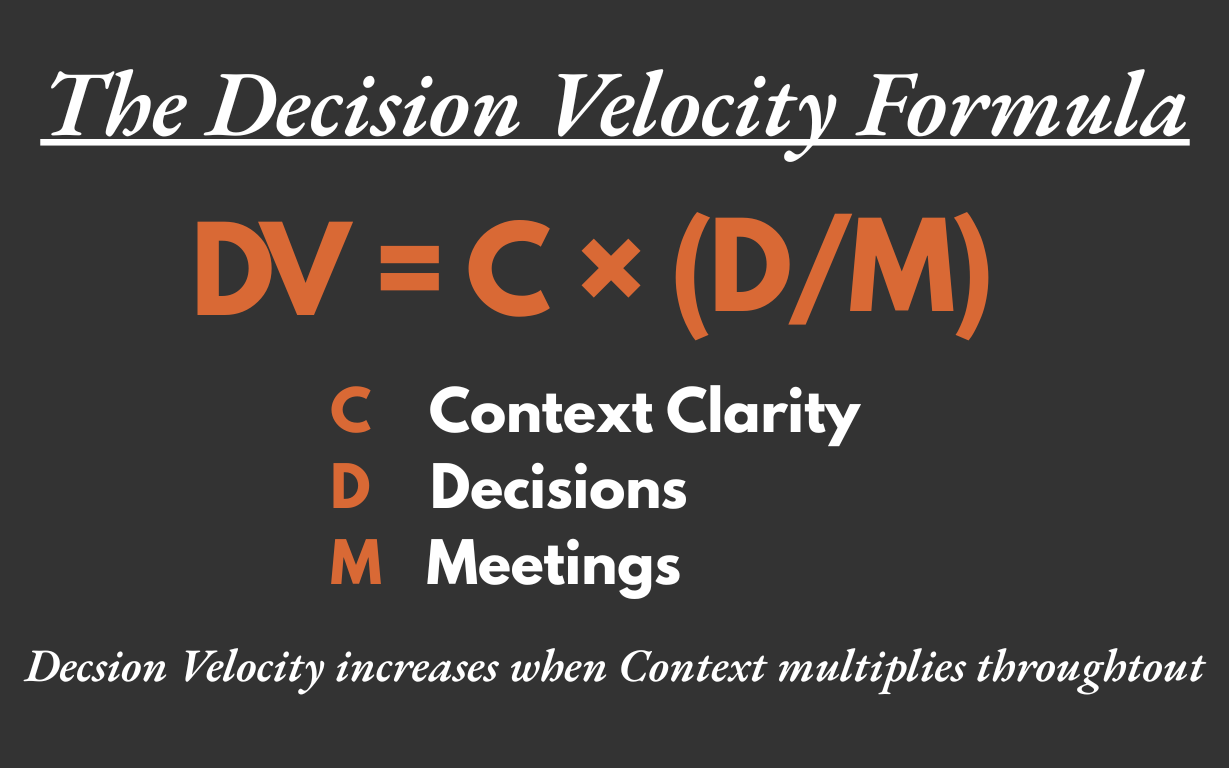

DV = C × (D/M)

Where:

C = Context clarity (how aligned the team is on what customer transformation they own)

D = Strategic decisions made

M = Meetings required to make them

DV = Decision Velocity

The D/M ratio is throughput. More decisions per meeting, less coordination overhead.

Founders don’t move faster because they work more hours. They move faster because they make more decisions per hour—and every decision requires fewer coordination meetings.

Same meeting, different output. Same week, 10x the decision count.

Here’s what that looks like inside the room.

Inside the Meeting Room

Imagine two meetings. Same agenda. Same company. Different leaders.

The Professional Manager’s Meeting

Marketing brings a channel decision to the table. The VP has prepared a solid deck—market data, competitive analysis, budget scenarios.

The discussion starts: “Which channel should we prioritize for Q2?”

Hands go up. Questions follow.

“What’s our customer acquisition cost target?”

“How does this align with the product roadmap?”

“Can we get more data on competitor spend?”

Good questions. Necessary questions. But each one requires follow-up. The meeting ends with three action items and a follow-up session scheduled.

One decision attempted. Zero decisions made. Two more meetings to go.

The Founder’s Meeting

Same agenda arrives. Same deck. Same data. One meeting to decide what took three meetings to defer.

The founder listens for two minutes, then starts working through the decision out loud:

“Which channel reaches operations managers who are missing moments that matter? LinkedIn—that’s where they’re scrolling at 10pm when they should be sleeping.”

“What message? Stop choosing between your calendar and your family.”

“What offer? Free trial positioned around eliminating the excuse to stay late.”

“When do we launch? Before Q2 planning locks in—three weeks.”

Four decisions. One meeting. Same hour, completely different output.

The professional manager isn’t slower because they’re less intelligent. They’re slower because they’re missing the filter.

They know company goals. They know department metrics. They know competitive landscape.

What they don’t know: who the customer becomes when they succeed.

Without transformation context, every decision requires triangulation. You need more data. More input. More alignment meetings. Not because you’re thorough—because you don’t have the filter that makes the right answer obvious.

The founder walks into that room knowing James. Knowing the soccer games James can’t miss. Knowing his weekend experience. And knowing the transformation the product enables.

That context doesn’t just inform decisions. It makes decisions. The filter does the work.

Not because founders are smarter. Because they carry context that eliminates the need for clarifying questions.

But where does that context come from? And if it's this powerful, why do so few companies have it?

The Context Gap

Bain’s 2016 research identified three characteristics. Each one spawned its own management philosophy. And each one got codified incompletely.

Thread 1: Business Insurgency → Founder Mode

Bain saw founders staying hands-on. Skipping management layers. Attending to details that “professional” CEOs delegated away.

Graham’s “Founder Mode” essay codified this observation into permission: founders should stay involved, not retreat to the executive suite.

What this captures: the behavior of founder engagement.

What it misses: why that engagement produces better decisions. Staying hands-on doesn’t automatically create 4 decisions per meeting. Micromanagers attend every detail. Still slow.

The behavior is visible. The mechanism isn’t.

Thread 2: Front-line Obsession → Customer Obsession

Bain saw founders maintaining direct customer contact. Jeff Bezos codified this into Amazon’s famous principle: “Start with the customer, work backwards.”

Customer obsession became gospel. Companies built research departments. Conducted surveys. Created personas. Mapped customer journeys.

What this captures: the orientation toward customer understanding.

What it misses: customer obsession doesn’t explain velocity. Companies can be obsessively customer-focused and still take 10 meetings to make 4 decisions. The research, the surveys, the personas—they often increase meeting count rather than decrease it.

More customer data doesn’t automatically create decision density. Something else is required.

Thread 3: Owner’s Mindset → Ownership Culture (The Misread)

This is where the codification went sideways.

Bain observed founders acting with “speed to act” and “personal responsibility for risk and cost.” They saw ownership behavior—decisive action, accountability, long-term thinking.

What got codified: Restricted stock units (RSUs) and equity stakes. “Act like you own the company.”

The problem: all of this points inward. It’s company-facing ownership. Own your department. Own your decisions. Own your equity.

But the founders Bain studied weren’t just owning the company. They were owning something else entirely.

The Missing Thread

All three threads point to the same gap.

Founder Mode captures hands-on behavior—but doesn’t explain why founders know which details matter.

Customer Obsession captures orientation toward customers—but doesn’t explain why founders make faster decisions from the same customer data.

Owner’s Mindset captures decisiveness—but doesn’t explain what founders are actually decisive about.

The missing piece isn’t about owning the company.

It’s about owning the transformation.

Transformation Ownership: The Unifying Mechanism Behind Decision Velocity

The founder in that meeting room didn’t just know James existed. They knew who James becomes when the product works.

James stops missing soccer games. James gets his weekends back. James stops dreading the Sunday night email check.

That’s not customer obsession. Customer obsession asks: “What does the customer need?”

Transformation ownership asks: “Who does the customer become?”

The difference sounds semantic. It’s not.

Customer obsession keeps you focused on where customers are—their current problems, their feature requests, their pain points. It’s present-tense orientation.

Transformation ownership requires you to see where they’re going—the journey they’re on, the identity change they’re pursuing, who they become when they succeed. It’s future-tense clarity.

Why transformation ownership makes all three Bain characteristics work.

This is why Business Insurgency works. Founders aren’t rebelling against management norms randomly. They’re insurgents on behalf of a specific customer transformation they’ve claimed as territory. They skip levels and attend to details because those details affect whether James makes his daughter’s game.

This is why Front-line Obsession works. Founders aren’t collecting customer data for research decks. They're maintaining contact with the transformation they own—watching where customers get stuck, seeing them progress, recognizing what blocks the identity change.

This is why Owner’s Mindset works. Founders aren’t just personally accountable for company outcomes. They’re personally accountable for whether customers achieve the transformation. James’s soccer games aren’t a persona insight. They’re a promise.

Transformation ownership is the context that makes all three characteristics velocity-producing—not just culturally admirable.

The Decision Velocity Math

C (Context Clarity)= Transformation ownership clarity. Founders know which customer transformation they own. Professional managers inherited a strategy deck that describes products, not transformations.

D (Decisions Made) increases because transformation ownership provides the filter. The right answer becomes obvious. James → LinkedIn → “Stop choosing between your calendar and your family.”

M (Meetings Required) decreases because transformation ownership eliminates triangulation. No need for follow-up sessions when the context makes decisions self-evident.

Bain's three characteristics aren't cultural aspirations. They're how you build transformation ownership. Which is how you build velocity.

But what does transformation ownership actually look like when you operationalize it? How specific does “knowing the customer” need to be?

More specific than most companies ever get.

The Specificity Needed for Decision Velocity

Most companies describe what they do. Few companies describe who their customer becomes.

Watch the difference:

Time-Tracking Software

Abstract thinking: “We help businesses track employee hours and improve operational efficiency.”

Transformation thinking: “James makes his daughter’s soccer games, and stops dreading the conversation with his wife about why he’s working late again.”

Same product. Completely different decision filter.

“Improve operational efficiency” doesn’t tell you which channel to prioritize. It doesn’t tell you what message to lead with. It doesn’t tell you when to launch or what offer to make.

“James makes his daughter’s soccer games” tells you everything.

Accounting Platform

Abstract thinking: “We streamline financial operations and reduce month-end close time.”

This is accurate. It’s also useless for making decisions.

Transformation thinking: “Maria stops waking up at 3am the week before month-end. Her CFO stops micromanaging the numbers. The board meeting becomes a conversation instead of an interrogation.”

Same product. Much clearer decision filter.

How Specificity Creates Velocity

When you know James—really know him—decisions stop requiring meetings.

Which channel?

The one reaching operations managers who are missing moments that matter. LinkedIn, where they’re scrolling at 10pm instead of sleeping. Not Instagram. Not TikTok. Not broad-reach display ads.

What message?

“Stop choosing between your calendar and your family.” Not “improve operational efficiency.” Not “streamline your workflow.” The message that hits James in the chest.

What offer?

Free trial positioned around eliminating the excuse to stay late. Not “14-day free trial.” Not “see pricing.” The offer that removes the barrier between James and his daughter’s game.

When to launch?

Before Q2 planning locks budgets in. When operations managers are feeling the weight of another missed season. Not “when the product is ready.” When James is ready.

What feature to prioritize?

The one that eliminates Sunday night email dread. Not the one with highest upvote count on the feature request board. The one that delivers the transformation.

Five decisions. One transformation story. No follow-up meetings required.

This is the specificity level that makes the filter work: knowing James and Maria as people pursuing transformation, not personas representing segments.

Abstract positioning creates decision paralysis:

Every option seems plausible

Every direction needs more data

Every choice requires alignment meetings

Transformation ownership creates decision clarity:

Options filter themselves

Direction emerges from the story

Choices become obvious to everyone in the room

Clarity is velocity. Not a metaphor. The mechanism.

This is what high C (Context Clarity) looks like in the Decision Velocity Formula.

High context clarity eliminates the questions that require follow-up meetings. When everyone sees James’s transformation clearly, ‘Which channel?’ has an obvious answer. No debate. No data requests. No coordination overhead.

That’s how C multiplies the D/M ratio. Context clarity removes the meetings (M ↓) while enabling more decisions per meeting (D ↑).

This is why the founder made 4 decisions in one meeting while the professional manager made 0. The founder wasn’t smarter. They had higher C.

But here’s the question this raises: Does every decision have to be right?

The counterintuitive answer is no. And that’s where the real advantage lives.

The More At-Bats Advantage

Here’s what the math reveals that most people miss:

Prime Movers don't win because every decision is perfect. They win because they get more at-bats.

Who's a Prime Mover? The individual whose decision patterns predict category ownership. Not the loudest voice. Not the highest title. The person who makes the kind of decisions that create category owners—before anyone realizes the category exists.

The professional manager making 0 decisions per meeting isn’t just slower. They’re getting fewer at-bats. Fewer experiments. Fewer chances to learn. Fewer opportunities to course-correct.

The founder making 4 decisions per meeting isn’t necessarily making better decisions. They’re making more decisions—which means more feedback, more data, more learning cycles compressed into the same timeframe.

But here’s the critical part: decision velocity works when meeting count stays low.

Four decisions made across four meetings = same velocity as one decision in one meeting. The math doesn’t lie: 4/4 = 1/1.

The advantage isn’t just making more decisions. It’s compressing decisions into fewer coordination cycles.

This is the D in DV = C × (D/M). Decision count matters. But only when you’re not adding meetings proportionally.

This is the paradox: Decision velocity doesn’t require decision accuracy. It produces decision accuracy through iteration speed.

The Moneyball Principle

Billy Beane didn’t build the Oakland A’s around batting average. He built them around on-base percentage.

The insight: Getting on base matters more than how you get there. A walk counts the same as a hit. What matters is at-bats that lead to base runners.

Traditional baseball valued the quality of each swing—the perfect hit, the beautiful stroke. Beane valued the quantity of opportunities—more ways to get on base meant more chances to score.

Decision velocity works the same way.

Traditional management values the quality of each decision—the perfect analysis, the airtight business case. Prime Movers value the quantity of decisions—more choices made means more learning captured means more course corrections possible.

Remember the founder’s meeting: 4 decisions in one hour. Channel, message, offer, timing. Not perfect decisions—testable decisions.

The professional manager’s meeting: 0 decisions, 3 action items, 2 follow-up meetings scheduled. Pursuing perfect analysis while the founder is already learning from real market feedback.

When you move at 4 decisions per meeting, you can afford to be wrong.

The Affordability to “Swing and Miss”

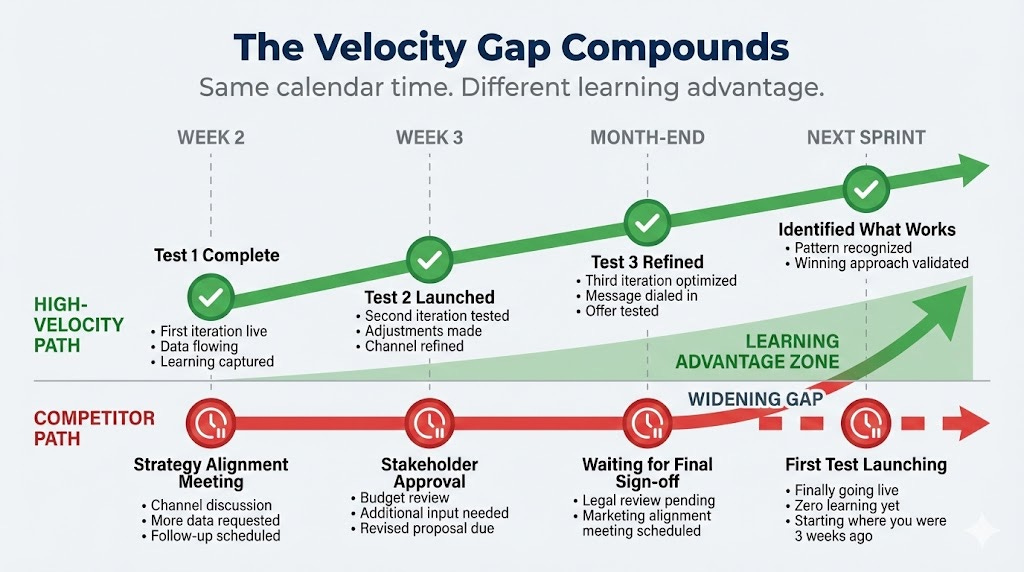

This is what velocity actually buys: the ability to be wrong without it being fatal.

Miss on channel selection? You’ll know in week 2. Adjust in week 3. Message doesn’t land? You’ll see it in the data. Revise by month-end. Offer underperforms? Test a new one next sprint.

Your competitor moving at 0.5 decisions per meeting?

Week 2: Still in the strategy alignment meeting.

Week 3: Waiting for stakeholder approval.

Month-end: Finally launching their first test.

Next sprint: You’ve already run three iterations and identified what works.

High-velocity organizations don’t need perfect decisions. They need fast decisions with fast feedback loops. The learning compounds while corrections accumulate. The accuracy emerges from iteration, not from analysis.

Low-velocity organizations need every decision to be right—because they can’t afford to be wrong. Each choice carries enormous weight. Each mistake takes quarters to correct. So they analyze more, meet more, delay more. M climbs. D/M collapses. Velocity disappears.

The irony: The pursuit of perfect decisions creates the conditions where mistakes become catastrophic.

4x velocity doesn’t mean 4x better decisions. It means 4x more learning. 4x more adaptation. 4x more opportunities for the market to teach you what works.

Which reveals what the real competitive moat actually is.

It’s not decision quality. It’s not even decision quantity.

It’s the ability to make high-volume decisions without coordination overhead.

That’s where M comes in.

The M Factor: Coordination Overhead Elimination

M is coordination overhead. Meetings required. Alignment sessions. Stakeholder reviews. The organizational friction between “decision needed” and “decision made.”

High-M organizations aren’t slow because their people are slow. They’re slow because every decision requires synchronization across departments, approval chains, and calendar availability.

What Low M Looks Like

The founder’s meeting from earlier had M = 1.

No pre-meeting to align stakeholders. No follow-up session to finalize decisions. No coordination with other departments before making the call.

Channel, message, offer, timing—all decided in one hour because everyone in the room shared James’s transformation context. The context was the coordination.

The professional manager’s meeting had M = 3 (and climbing).

Initial meeting to discuss options. Follow-up session after gathering more data. Final alignment meeting once stakeholders reviewed the proposal. And that’s just for ONE decision—the channel choice.

Same question. Same data. Different M.

What creates the difference? Low-M organizations move fast because context is already distributed. When everyone knows James—knows the transformation, knows what they’re building toward—decisions don’t require alignment meetings. The shared context is the alignment.

This is why C multiplies D/M in the formula. Context clarity doesn’t just increase decisions made. It decreases meetings required. The numerator goes up. The denominator goes down. Velocity compounds.

Good addition. It’s diagnostic, connects to your owned language (rented positioning, abstract strategy), and explains the mechanism readers can self-assess against. Let me integrate it:

What Creates High M

Rented positioning: When you compete on variables someone else defined, every decision requires validation. “How does this compare to competitors?” becomes a coordination question. You’re not deciding based on your transformation story—you’re deciding based on category norms that require constant rechecking.

Abstract strategy language: “Improve operational efficiency” means something different to Marketing, Product, and Sales. Each interpretation conflict triggers alignment meetings. The strategy deck creates the illusion of shared context while actually producing coordination overhead.

Inherited strategy: Professional managers get handed positioning they didn’t create. The transformation context lives in a deck, not their heads. Every decision requires checking the deck, confirming with stakeholders, validating alignment.

Founders avoid this naturally. They built the transformation story. It’s distributed context, not documented strategy.

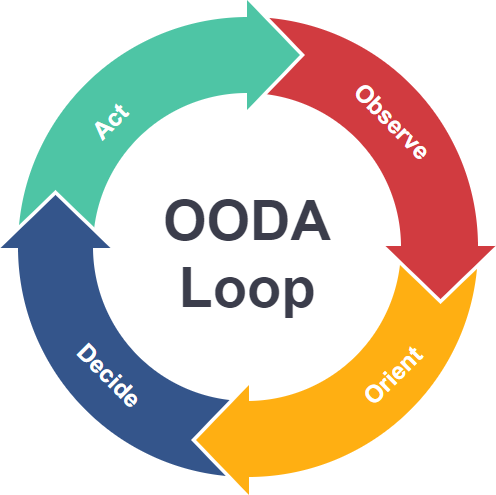

The OODA Advantage

Fighter pilot John Boyd built his reputation on a simple insight: the pilot who cycles through Observe-Orient-Decide-Act faster wins the dogfight.

Not the pilot with better aim. Not the pilot with the superior aircraft. The pilot with faster decision tempo.

Boyd’s insight wasn’t just about deciding faster. It was about eliminating the coordination overhead between observe and act.

Traditional military doctrine: Observe → Report to command → Wait for orders → Coordinate with other units → Act.

Boyd’s approach: Observe → Orient using pre-established doctrine → Decide independently → Act immediately.

The shared doctrine (context) eliminated the coordination steps. High C enabled low M.

Decision velocity works the same way in organizations.

By the time your competitor finishes their analysis, you’ve already tested three approaches. By the time they align stakeholders, you’ve already learned what works. By the time they launch, you’ve already iterated past the version they copied.

Remember the timeline from earlier: Your competitor at 0.5 decisions per meeting is still in strategy alignment while you’ve completed three learning cycles. Week 2 vs. Week 2. Month 1 vs. Month 1. Same calendar time, 4x the learning advantage.

They’re not behind because they started later. They’re behind because they can’t catch up. Every decision cycle you complete while they’re still coordinating extends your learning advantage.

The System Effect: How C, D, and M Interconnect

This is the full Decision Velocity Formula:

DV = C × (D/M)

High C (transformation ownership clarity) acts as the multiplier. When everyone knows James’s transformation, channel decisions become obvious, message decisions become obvious, timing decisions become obvious.

High D (decision volume) creates learning velocity. Four decisions per meeting means four experiments, four data points, four opportunities to course-correct.

Low M (minimal coordination) enables compression. One meeting making four decisions beats four meetings making four decisions. Same D, quarter the M, 4x the velocity.

The variables aren’t independent. They’re interconnected:

Low C forces high M - Unclear context = clarifying questions = follow-up meetings. Coordination overhead multiplies.

High M prevents high D - Coordination overhead creates decision bottlenecks. If every choice requires three alignment meetings, decision volume collapses. You can’t make 4 decisions per meeting when each decision needs 4 meetings.

High C enables both high D and low M - When everyone knows James’s transformation story, channel decisions are obvious. Message decisions are obvious. Timing decisions are obvious. No clarifying questions. No alignment sessions. No coordination overhead.

This is why transformation ownership isn’t just helpful. It’s the foundation of the entire system.

And here’s what makes this powerful: you don’t need to be a founder to build it.

The real moat isn’t being right. It’s being able to be wrong faster.

Competitors can study your strategy. They can copy your positioning. They can hire your playbook.

What they can’t copy is the velocity infrastructure that let you discover that strategy in the first place. By the time they implement what worked for you six months ago, you’ve already learned what works now.

Learning velocity compounds: each iteration teaches you something that makes the next iteration faster, sharper, more targeted.

Coordination overhead compounds too—in the wrong direction. Each meeting adds to the calendar, which requires more coordination for the next decision, which adds more meetings. The spiral accelerates.

The gap doesn’t close. It widens.

But here’s the part that changes everything: this advantage isn’t founder DNA. It’s buildable infrastructure.

How to Build Founder-Level Context

You don’t need to BE a founder. You need to BUILD the context founders carry.

The founder in that meeting room didn’t make 4 decisions because of charisma or hustle or years of experience. They made 4 decisions because they carried transformation context that made the right answers obvious.

That context isn’t mystical. It’s specific:

Who transforms (James, Maria, Sarah)

What they’re escaping (missed soccer games, 3am anxiety, weekend reports)

Who they become (present parent, confident CFO, respected leader)

What unlocks the shift (the product, positioned correctly)

Founders build this context naturally through the founding process. They talked to the first customers. They felt the first transformation. They carry James in their heads because they were there when James’s life changed.

Professional managers inherit a strategy deck. Founders inherit a transformation story.

The question isn’t whether transformation context creates velocity. The data proves it does—3.1x over 15 years.

The question is: can you build it deliberately?

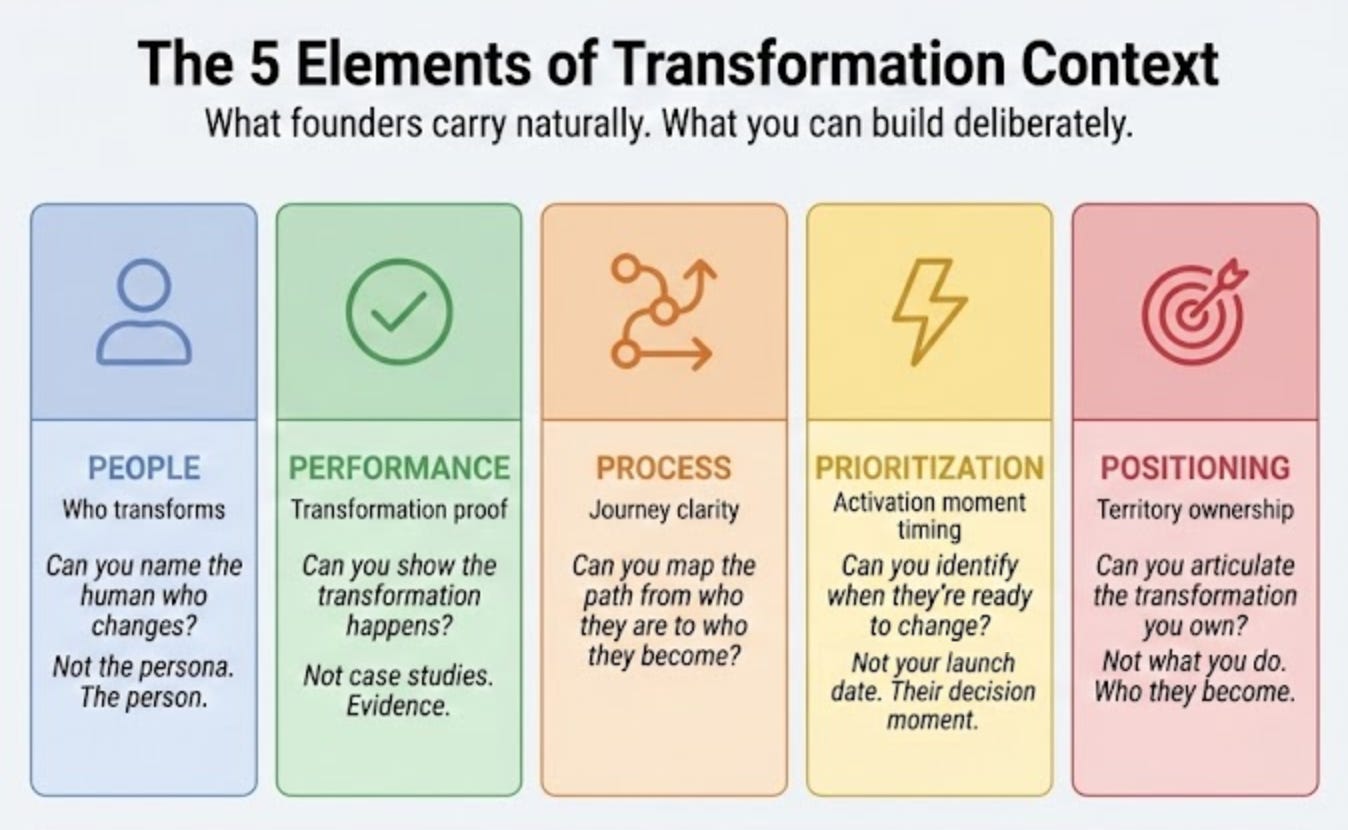

The 5 Elements of Transformation Context

Transformation context has five elements. Build them, and you build the clarity founders carry naturally:

People specificity → Higher C (everyone knows James, not "operations managers")

Performance validation → Higher C (transformation proof, not case studies)

Process mapping → Higher C (journey clarity eliminates "how do we get there" questions)

Prioritization timing → Higher C (activation moment clarity focuses decisions)

Positioning ownership → Higher C (territory clarity eliminates competitive triangulation)

More elements built = higher C = fewer coordination meetings (M↓) = more decisions per meeting (D↑) = higher velocity.

These five elements are the Strategy Flywheel—the systematic framework for building transformation context.

The Truth About the Founder 3.1x Performance Advantage

This is what Bain measured but couldn’t explain.

Founder-led companies don’t outperform because founders work harder. They outperform because founders carry transformation context that enables:

Higher C → They know the transformation they own

Higher D → Context makes decisions obvious, so more get made

Lower M → Shared context eliminates coordination overhead

DV = C × (D/M)

The formula explains the 3.1x. Transformation ownership is the mechanism. Decision velocity is the output.

The 3.1x advantage isn’t founder DNA. It’s transformation context that can be built.

The 5 elements make founder-level decision velocity accessible to anyone willing to do the work. Not because you become a founder—but because you build the infrastructure founders carry naturally.

Start with one question: Which element would unlock the most velocity for you right now?

If you can’t name the human who transforms → start with People.

If you can’t prove the transformation happens → start with Performance.

If you can’t map the journey → start with Process.

If you can’t identify the activation moment → start with Prioritization.

If you can’t articulate the territory you own → start with Positioning.

Start with one element. Build it to human-level specificity—not abstract strategy language, but James-level detail. Then add the next.

Transformation context isn’t built in one session. It’s built through systematic work on each element until the context becomes distributed across your team.

Closing each context gap creates clarity. And clarity is velocity.

PS - The hardest part of building decision velocity isn't understanding the formula—it's diagnosing which variable to fix first. What's your hypothesis for your team? (My bet: most teams think it's D, but it's actually C.)