Clarity Is Velocity: The Movement You Build Begins With What You Own

Prime Positioning - Episode 6: Owners set the rhythm. Renters watch competitors.

Prime Positioning - Episode 6

The movement you build begins with what you own

James has 52 days left and a team that finally sees the transformation customers need. But before they can build toward it, Sam asks one question that exposes three years of strategic drift—and why fast execution on rented territory never compounds into competitive advantage.

James watched his team settle in. The same energy he’d felt after his first conversation with Sam—when scattered frustration crystallized into pattern recognition.

They’d spent the evening processing the eight customer calls he’d made weeks ago. Every customer said it in different words: they needed decision velocity, not dashboards.

Sam arrived at nine, surveying their prepared materials with a nod. “You see it now,” he said. “The summit they’re actually seeking.”

“Decision velocity,” the Product VP said. “Every customer James talked to. Different words, same destination.”

“Good.” Sam moved to the whiteboard where yesterday’s flywheel diagram still remained—five elements circling, connections visible but not yet understood. “That clarity will matter. But not yet.

“Before we build forward,” Sam continued, “we need to understand where Dayanos actually stands. The transformation is clear. The question is: what do you own that lets you deliver it?”

He tapped the flywheel.

“Yesterday I introduced this. Five elements that connect. Today we run Dayanos through it—not theory, not best practices. Your actual position. What you actually own.”

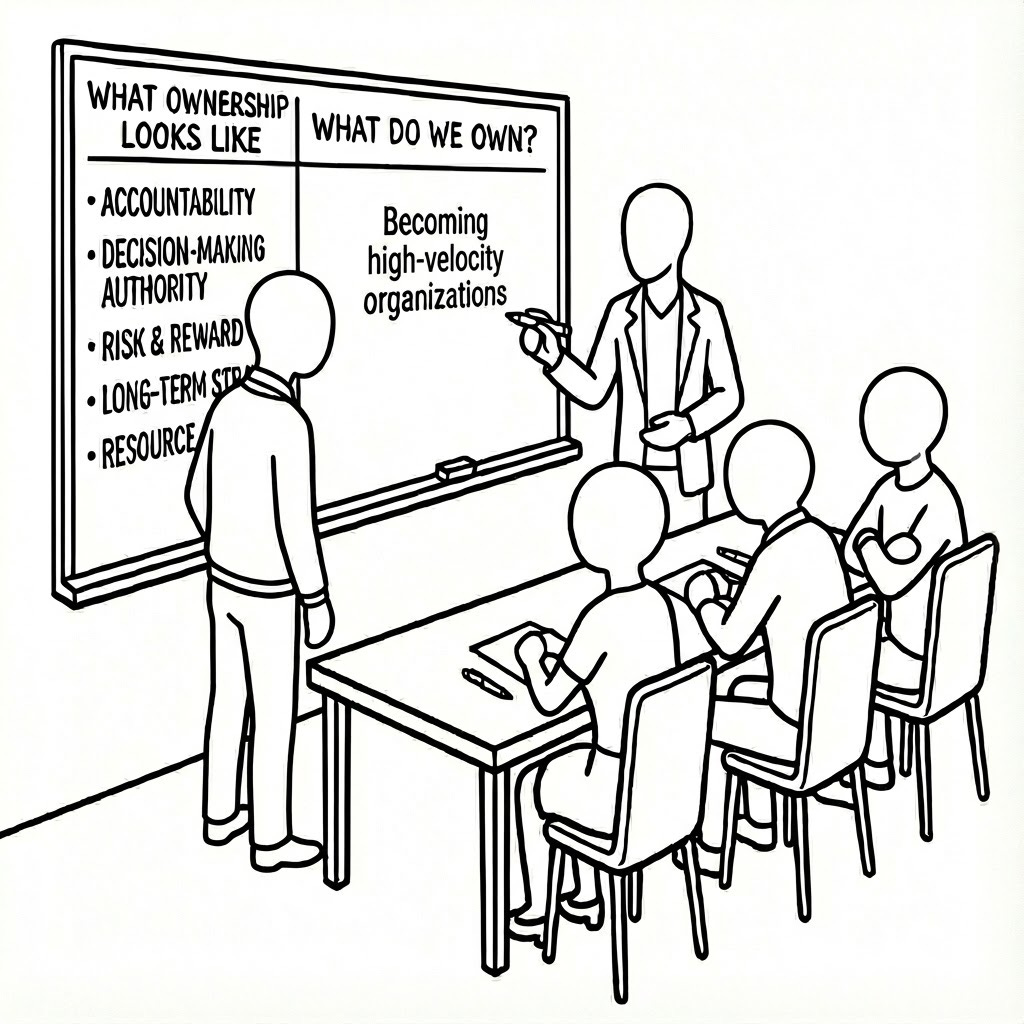

Sam drew a vertical line next to the flywheel, dividing the whiteboard in two. He wrote at the top of each column:

WHAT OWNERSHIP LOOKS LIKE | WHAT DO WE OWN?

“At every element, there’s a question: What do you own here? Not what you do. Not what you’re good at. What territory is yours?” He looked around the room. “Most companies have never asked this question. They’re too busy executing to notice they’re building on ground someone else controls.”

The Product VP set down his pen.

“This will be uncomfortable,” Sam said. “You’re going to look at each element and ask what you own. The answer might be... less than you expect.”

He looked around the room.

“The goal isn’t blame. It’s clarity. Once you see what you own—and what you don’t—you’ll understand why some companies move with confidence while others are always reacting.”

Know What You Actually Own

Sam pointed to the first element on the flywheel.

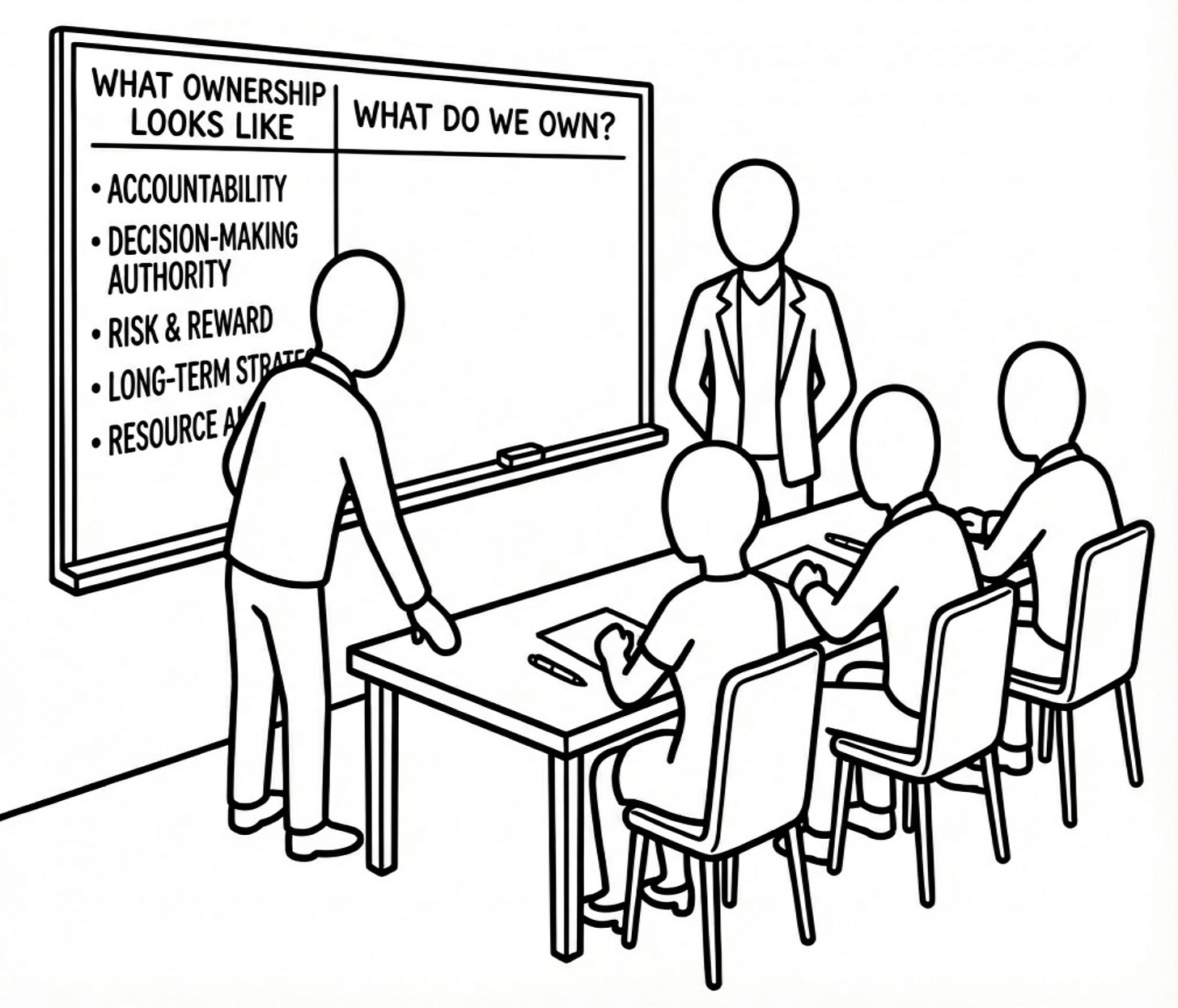

“People. Let’s start here.” He wrote in the left column:

WHAT OWNERSHIP LOOKS LIKE: A transformation story that customers can only get from you. Language that defines the journey. A summit you own.

“That’s what ownership looks like at this element. A transformation customers seek that only you deliver.” He turned to face the team. “So. What transformation do you own?”

Nobody moved.

The Product VP shifted. “We help customers get visibility into their distributed team coordination. AI-powered meeting intelligence. Automated summaries.”

“Those are capabilities,” Sam said. “I asked what transformation you own. What do customers become because of you—that they couldn’t become any other way?”

The Engineering Director stopped writing.

The Marketing VP pulled up an old pitch deck. “Our launch messaging was ‘Dayanos gives your team AI-powered visibility into every meeting, every decision, every action item. Never lose track of what matters.’”

Sam looked at the right column. He didn’t write anything.

“Now think about Amalakai. How do they talk about their customers?”

The Engineering Director had been researching competitors for months. “They say things like ‘decision intelligence for the modern enterprise.’ Their tagline is ‘From insight to action, faster.’”

“And a dozen other competitors? What do they say?”

“Similar things. AI-powered. Visibility. Intelligence. Faster decisions.”

Sam tapped the empty right column. “You’re all describing the same territory. Different features, same borrowed ground.” He turned to face them. “When everyone uses the same language, no one owns it. You’re all paying rent to compete in a category none of you defined.”

He wrote in the left column under ownership:

vs. Feature language that validates shared category territory

“See the difference? Transformation ownership means customers come to you because they want to become something specific—something only you can help them become. Feature positioning means they’re comparing you to alternatives. Evaluating. Shopping.”

The Product VP was staring at the empty column. “We don’t own a transformation. We compete on features in a category someone else defined.”

“What about Amalakai?” James asked. “Do they own it?”

Sam paused. “They own ‘decision intelligence.’ But that’s a tool category. Helping companies make faster decisions. It’s better positioning than yours—but it’s still a what, not a who-they-become.”

He tapped the empty right column again.

“The transformation your customers described—becoming organizations that make faster decisions systematically—no one owns that. It’s available territory.” He paused. “But that’s not what we’re diagnosing right now. Right now we’re seeing what Dayanos owns.”

He looked at the whiteboard. Left column: what ownership looks like. Right column: empty.

“Let’s keep going.”

Sam pointed to the next element.

“Performance. What do you own here?”

He wrote in the left column:

WHAT OWNERSHIP LOOKS LIKE: Signals that predict transformation progress. Metrics that only matter if your specific transformation is happening. Evidence that customers are becoming what they sought to become.

“That’s ownership at this element. Signals that are yours—that only make sense if customers are on your transformation journey.” He turned to the team. “What signals do you own?”

The Engineering Director answered. “We track usage. Logins, feature adoption, time in app. Customer satisfaction scores. For Dayanos specifically—meetings captured, summaries generated, action items tracked.”

Sam looked at the right column. He didn’t write anything.

“Do your competitors track the same things?”

“Probably. These are standard SaaS metrics.”

“So if a customer has high usage of your product and high usage of a competitor’s product—these signals wouldn’t tell you the difference?”

The Marketing VP looked at her colleagues. Same recognition on every face.

The Product VP said quietly, “Ramorian had green across the board. Highest-usage account. Generating more summaries than almost anyone. Satisfaction scores were positive. And they left.”

“Your measurement system told you everything was fine. Until it wasn’t.” Sam tapped the empty column. “You don’t own these signals. Everyone measures them. They tell you activity is happening—not that transformation is happening.”

He wrote in the left column:

Non-obvious signals: Decision cycle time. Decision durability. Coordination overhead trends.

“These would be owned signals. They only matter if customers are becoming high-velocity organizations. If that’s not the transformation—these metrics are meaningless.” He looked at the team. “But if it is your transformation, these are the signals that predict success before revenue confirms it.”

The Marketing VP made the connection. “We celebrated when Ramorian hit 90% meeting capture. We thought that meant success.”

“It meant activity,” Sam said. “Activity at base camp. Not progress toward a summit.”

He looked at the right column. Still empty.

“You’re measuring what the category measures. Which means you’re optimizing for the category’s definition of success—not transformation success that would be uniquely yours.”

Renters React to the Owner’s Rhythm

Sam pointed to the third element.

“Process. What do you own here?”

He wrote in the left column:

WHAT OWNERSHIP LOOKS LIKE: Shared context that enables autonomous decisions. Distributed understanding of the transformation you’re delivering. People making aligned choices without coordination meetings because they see the same picture.

“That’s ownership. When context is owned, it’s everywhere. People don’t need approval chains because judgment is already aligned.” He looked at the team. “What context do you own?”

The Engineering Director didn’t hesitate. “We have process. Product review boards. Architecture councils. Go-to-market alignment meetings. Cross-functional syncs.”

“That’s coordination structure. I asked what context you own—what shared understanding exists that lets people make autonomous decisions?”

James answered slowly. “We built all that process because people didn’t share context. Engineering would build something Product didn’t want. Marketing would launch campaigns that didn’t match what we shipped.”

“So you built decision support,” Sam said. “Structures to force alignment. Reviews. Approvals. Checkpoints.”

“Yes. It reduced mistakes.”

“Did it? Or did it just move the cost somewhere else?”

The Engineering Director: “Time. Everything takes longer than it did two years ago.”

The Marketing VP: “Meetings. My team jokes we have meetings to prepare for meetings.”

Sam looked at the right column. He wrote nothing.

“You don’t own shared context. You manufacture alignment through process.” He wrote in the left column:

vs. Decision support: Approval chains, coordination overhead, manufactured alignment

“Companies that own transformation context move fast because everyone sees the same picture. The founder’s context is everyone’s context. Decisions happen at the edge because judgment is already aligned.”

He stepped back from the board.

“You have process instead of context. That’s not ownership—that’s coordination tax. Paid every week, in every meeting, because people don’t share the transformation understanding.”

The Engineering Director did the math. “Thirty hours a week of cross-functional coordination meetings across leadership alone.”

“Thirty hours of tax,” Sam said. “Because there’s no shared context to own.”

Sam pointed to the fourth element.

“Prioritization. What do you own here?”

He wrote in the left column:

WHAT OWNERSHIP LOOKS LIKE: THE constraint. The single thing that matters most for the transformation you own. A filter that makes every other decision obvious.

“That’s ownership. One constraint that clarifies everything else.” He looked around the room. “What constraint do you own?”

The answers came from different directions.

“Enterprise expansion,” the Product VP said. “We need to move upmarket.”

“Product-led growth,” the Marketing VP countered. “Self-service is how we scale.”

“Platform stability,” the Engineering Director added. “Technical debt is slowing us down.”

James listened. “And I’ve been pushing competitive response. Amalakai is taking deals.”

Sam let the silence hold. “That’s four different priorities from four people. In one room. On one leadership team.”

He looked at the right column. Wrote nothing.

“Which one is THE constraint?”

“They’re all important,” the Product VP said. “We can’t ignore any of them.”

“So you’re optimizing for all of them. Simultaneously.” Sam drew four arrows pointing in different directions. “Enterprise wants high-touch sales. Product-led wants frictionless self-service. Platform stability wants engineering time. Competitive response wants fast pivots.”

He wrote in the left column:

vs. All constraints: Multiple priorities competing, fragmented attention, borrowed category demands

“You don’t own a constraint. You’re serving four different borrowed categories—each with its own demands, its own definition of winning.” He circled the empty column. “That’s why everything feels urgent. Each category is demanding attention. You’re paying rent in four different territories.”

The Marketing VP saw it. “We have four priorities because we’re competing in four different borrowed spaces.”

“And none of them are yours.”

Sam stepped back from the whiteboard.

Four questions. Four elements.

Left column full: What ownership looks like at each level.

Right column empty: What Dayanos owns.

The team stared at the whiteboard. The absence was louder than any accusation.

“Let me ask you something,” Sam said quietly. “Why have you been so focused on Amalakai?”

James started to answer—competitive threat, taking deals, board pressure—but stopped.

The Engineering Director saw it first. “Because we have nothing else to focus on.”

“Keep going.”

“We’re always watching them because...” She trailed off, looking at the empty column. “Because we don’t have territory of our own.”

Sam nodded slowly. “When you don’t own anything, all you can do is react. Track their moves. Match their features. Fight for deals on their terms. Celebrate when you win. Agonize when you lose.” He tapped the empty column. “You’ve been obsessed with Amalakai because obsession is what renters do. They watch the owners. They react to the owners. They define themselves relative to the owners.”

He drew a circle around the empty column.

“This is why. Not because Amalakai is good—though they are. Not because the market is competitive—though it is. Because you own nothing. You have no territory to defend, no transformation to deliver, no summit that’s yours. So you watch. You react. You compete on terms someone else set.”

The Marketing VP’s voice was quiet. “We’ve been renters. For three years.”

“Paying rent in categories someone else defined. Building equity for whoever owns the territory you’re competing in.” Sam let that settle. “Every feature comparison trained the market to evaluate on borrowed criteria. Every competitive win validated a category Amalakai also plays in. Every satisfied customer who described you as ‘AI-powered meeting visibility’ reinforced territory you don’t own.”

James felt the weight of it settle over the table.

“Renters don’t control their future,” Sam said. “They compete on terms someone else set. They win deals that validate someone else’s category. They lose deals for reasons they can’t change. They react to someone else’s rhythm instead of setting their own.”

He paused.

“And they’re always watching the competition. Because what else is there to watch?”

Ownership Creates Clarity

The room was still. The weight of three years of renting settling over everyone.

Then Sam tapped People on the flywheel.

“But you’re not renters anymore. Not now that you see the transformation.”

James looked up.

“James heard it in those calls weeks ago. Now you all see it. Customers want to become organizations that make faster decisions systematically. Not buy better tools. Become something.” Sam traced a line from People through the other elements. “That’s not borrowed language. That’s not what Amalakai says. That’s not what the category measures. That’s a transformation waiting to be owned.”

“And if we own that...” the Product VP started.

“Then everything else clarifies. You know what to measure—transformation progress, not feature adoption. You know what context to distribute—the journey from coordination-constrained to decision velocity. You know what constraint matters—whatever accelerates that transformation.”

Sam stepped back and wrote on the whiteboard:

CLARITY IS VELOCITY

“The diagnosis is the prescription. Same flywheel. Different starting point. When you own the transformation story, the empty column fills itself. Not with borrowed metrics and manufactured alignment. With signals and context and priorities that are yours.”

“The same cascade,” the Engineering Director said slowly. “But compounding in the other direction.”

“Rented choices create drift. Each element corrupts the next. You’ve been living that for three years.” Sam tapped the flywheel. “Owned choices create clarity. Each element reinforces the next. That’s what’s available now.”

James was quiet for a moment. Then:

“There’s something else here.”

Sam turned.

“Most companies learn a framework. Apply it. Follow the steps.” James gestured at the flywheel. “That’s still renting. Using someone else’s thinking structure.”

The Product VP looked up from her notes.

“The moment conditions change,” James continued, “they’re lost. The framework was a map. Not navigation capability.”

Sam said nothing. Waited.

“Owning is different. You stop asking ‘what does the framework say?’ You start asking ‘what does flywheel thinking reveal about this situation?’” James looked at his team. “Your people adapt the elements. Add what’s missing. Recognize the pattern in problems the framework never anticipated.”

He paused.

“That’s when a framework becomes a mental model. And mental models travel. They work without the person who taught it in the room.”

Sam let the silence hold for a moment.

“That’s exactly right.”

Clarity Is Velocity

James was staring at the flywheel. The same five elements. But now he saw them differently.

The empty column wasn’t an accusation. It was a map. It showed exactly where ownership needed to be built.

“We know the transformation,” James said. Not a question. A statement. “We heard it directly. Customers want to become organizations that make faster decisions systematically.”

He stood up. Moved to the whiteboard. Pulled up his notes from those customer calls weeks ago.

“They all said it differently,” he said quietly. “But they were describing the same transformation.”

“So if we own that transformation...” He traced the flywheel clockwise. “We measure decision velocity, not feature adoption. We distribute transformation context, not coordinate through meetings. We focus on the constraint that accelerates the journey, not everything our board mentions.”

He looked at the empty column.

“And we stop watching Amalakai.”

The room shifted.

“They’re competing on decision intelligence. Tools. Features. Better functionality.” James picked up a marker. In the empty column next to People, he wrote:

Becoming high-velocity organizations

“That’s not their territory. They help companies make faster decisions. We help companies become something. That’s a different category entirely.”

Sam said nothing. Just watched.

The Product VP leaned forward. “Amalakai can’t follow us there. Their whole business is built on the tool game. Every process, every metric, every priority.”

“They’d have to rebuild everything,” James said. “And they’re winning. You don’t rebuild when you’re winning.”

He looked at his team.

“We’re not winning. We have to rebuild anyway.” He tapped the whiteboard. “Might as well rebuild on territory we own.”

The team was watching James now. Not Sam.

Sam gathered his materials.

“You see the position now. You see what you don’t own. And you see the transformation that’s available.”

He looked at James.

“Tomorrow you start building ownership. Next pass through the flywheel. Given this territory, the question becomes: what must you focus on to claim it?”

The team gathered their notes slowly. The Engineering Director and Product VP were already sketching what ownership could look like at each element. The Marketing VP stood at the whiteboard, photographing the contrast between the two columns.

James stayed after they filtered out. The war room quiet now, late afternoon light cutting across the whiteboard.

Two columns. One full of what ownership looks like. One with a single entry—the transformation he’d written himself.

Becoming high-velocity organizations.

Three years of renting. Territory owned by others. Now: clarity. A transformation customers had described in their own words. Territory no one owned yet.

But clarity alone wouldn’t claim it. James looked at the empty column, then at his calendar.

51 days left.

Not 51 days to avoid losing another customer. But to claim territory before someone else does.

Available territory doesn’t stay available—someone would see it, claim it, own the transformation story customers were already seeking.

And tomorrow they’d discover if Dayanos has the ability to set the rhythm everyone else has to follow.

PRACTICE: The Ownership Audit

Time: 10 minutes

Most companies discover they’re renters when they ask what they actually own.

Try this right now: Pick one flywheel element. Ask: “What do we own here that competitors can’t claim?” Write what you discover in that silence.

Before your next strategy meeting: List your top three priorities. If a competitor could say the exact same thing, you’re renting their category—not owning territory.

AI Prompt:

For each area below, help me see whether we OWN strategic territory or RENT it from competitors:

Customer transformation we own: [What change do customers seek by working with us?]

(People)

Success signals we track: [What do we measure to know it’s working?]

(Performance)

How decisions get made: [What enables people to decide without endless meetings?]

(Process)

Our top priorities: [What are we optimizing for right now?]

(Prioritization)

Based on the ownership diagnostic:

- Which areas show we own unique territory vs. compete in borrowed categories?

- What would genuine ownership look like in our weakest area?

If we’re constantly watching competitors—what does that reveal about our position?

Help me see what I actually own.Next Episode: Claim Your Cadence (Now Live)

James’s team sees what they don’t own—and the transformation that’s available. Now they face the harder question: What must they focus on to claim it? With fifty-two days until the board meeting, they’ll design a strike that proves transformation ownership is more than words.

Subscribe to follow James’s transformation journey, and share with a leader who wants to build a movement on territory they actually own.

The diagnostic framework here cuts through by asking what you own vs what you optimize for. Most strategy decks list priorities without asking whether those priorities are even yours to claim, and the empty column exercise makes that brutaly visible. The renter-owner metaphor works because it gets at something deeper than competition: renters are always reactive becuase they're working within boundries someone else set, while owners get to define the game itself.