Claim Your Cadence: The Game You Choose Determines How You Move

Prime Positioning - Episode 7: Renters watch competitors. Owners set the game.

Prime Positioning - Episode 7

The Game You Choose Determines How You Move

James has 51 days left and a team that finally sees what they don’t own. Then he gets news about Ramorian—and the pressure to move fast threatens everything they just learned. Today James discovers the difference between competing on someone else’s terms and claiming territory they can’t touch.

James was up at 6:30 AM preparing for day three of the workshop. The positioning work. The strategic choices. 51 days until the board meeting.

James’s phone lit up at 6:35 AM. News alert.

Then another. Then a Slack notification from his chief of staff, marked urgent.

He opened the alert.

Amalakai in discussions with Ramorian for exclusive partnership. Sources confirm negotiations underway.

James read it twice. Then opened the chief of staff’s message.

Just saw the news. Ramorian meeting with Amalakai next week. Need to talk strategy.

Ramorian. The account they’d lost. The deal that triggered everything. And Amalakai—moving while Dayanos was still diagnosing.

He messaged his leadership team: Saw the news. We’ll talk about it this morning.

Then he grabbed his keys to rush into the office.

The energy in the war room was different when James arrived.

The Marketing VP was already at her laptop, Amalakai’s website open. The Engineering Director had the news article pulled up on his phone. The Product VP sat with his notebook closed, staring at the whiteboard where yesterday’s session had ended.

That empty column. What Dayanos didn’t own.

And what Amalakai was about to take.

“Okay,” James said, setting his bag down. “Everyone saw it.”

“Exclusive partnership.” The Marketing VP didn’t look up from her screen. “That’s way past exploratory stage.”

“How much time do we have?” the Product VP asked.

Constraints Reveal Your Real Strategy

The Engineering Director did the math. “If they’re announcing talks publicly? They’ve been working this for weeks. We’re not early. We’re late.”

James felt the familiar pressure building. The same pressure that had driven six months of fast execution in the wrong direction. The pressure that made you move without thinking.

“So we need to move fast,” the Marketing VP said. “Match their pitch. Show Ramorian we can deliver what they need again. Get in front of them before they sign.”

“How fast can we ship something?” the Product VP asked the Engineering Director.

“Depends what we’re shipping.”

“A demo. Proof of concept. Something that shows we’re not just dashboards anymore—we’re decision systems.”

The Engineering Director was already opening his laptop. “If we strip it down to core functionality... maybe six weeks for something credible. Eight weeks for something we’d actually want to show.”

“We don’t have eight weeks,” James said. “Board meeting’s less than two months out. If we lose Ramorian before then—”

“We need to get in front of them sooner,” the Marketing VP finished. “Which means we need something in... what, four weeks? Five?”

Sam walked in quietly. Set his coffee down. Looked at the whiteboard where yesterday’s work still remained—the Strategy Flywheel, the empty column showing what Dayanos didn’t own.

“We need a demo that beats Amalakai,” the Product VP said. “Four weeks, maybe five. That’s aggressive, but—”

“Why a demo?” Sam asked.

The room turned to look at him.

“You just spent two days diagnosing why fast execution didn’t work. You saw the pattern. Operating on rented territory, building equity for competitors.” Sam gestured to the whiteboard. “Renters compete on someone else’s timeline. Owners set their own cadence. Which are you choosing?”

“What else would we do?” the Engineering Director asked. “We can’t walk into Ramorian empty-handed.”

“You’re thinking about what to build. I’m asking what game you’re playing.” Sam moved to the whiteboard.

Then he drew two columns:

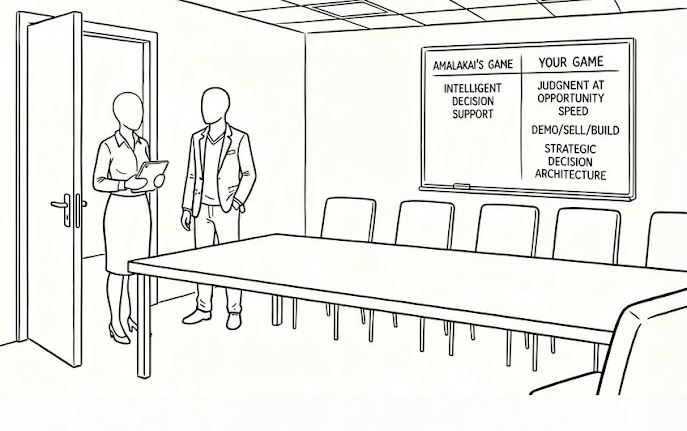

AMALAKAI’S GAME | YOUR GAME

“Amalakai is selling intelligent decision support. A tool. Features. They’re already ahead on that game—they have the product, the positioning, the relationships.” He tapped the left column. “If you compete on their terms, you’re playing catch-up. Again.”

“So what’s our game?” James asked.

“That’s what we’re here to figure out.” Sam looked around the room. “Yesterday you saw what you don’t own. Today you decide what you’re going to claim. But you can’t claim territory by competing faster in someone else’s category.”

The Marketing VP closed her laptop. “So we’re not building a demo.”

“I didn’t say that. I asked what you’re competing on. What game makes Amalakai’s strengths irrelevant?”

Silence. But not the scattered silence of confusion. The focused silence of a team working through something hard.

James thought about yesterday’s diagnosis. The empty column. The transformation customers had described in those eight calls weeks ago.

“Amalakai is selling them a tool,” James said slowly. “Better data, faster insights. But that’s not what customers told me they needed.”

“What did they need?”

“They needed to become something. Organizations that make high-quality decisions at opportunity speed. Not just better tools—transformation.”

Play Your Own Game

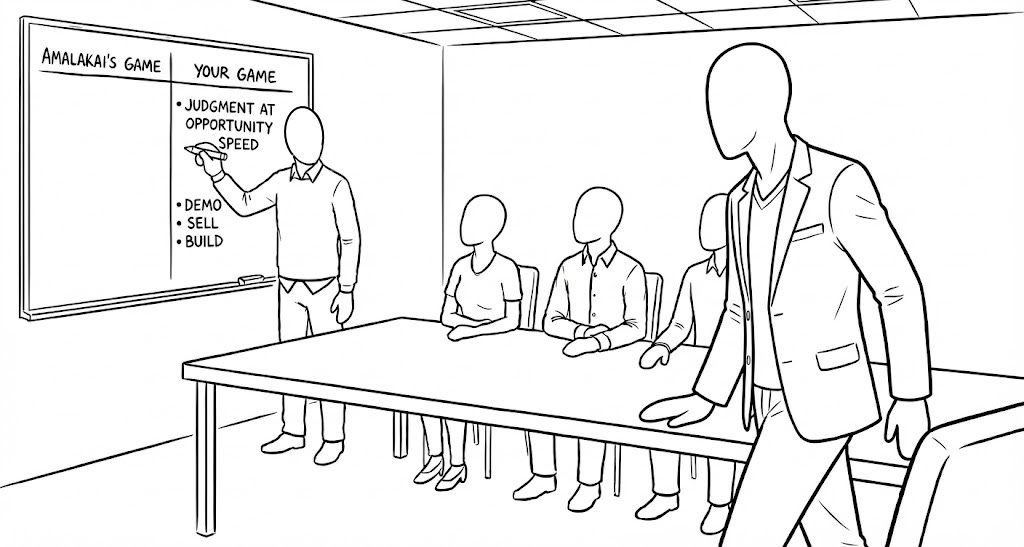

Sam wrote in the right column:

TRANSFORMATION

“Amalakai can’t sell that,” the Product VP said. “Their whole business model is tool-based. Software subscription, feature comparison, implementation timeline.”

“And if you try to out-tool them, you lose,” Sam said. “But if you claim transformation as your territory—if you prove you can help companies become high-velocity organizations—you’re playing a different game entirely.”

James felt something shift. “High-velocity organization. That’s what they actually want to become. But what does that mean in practice?”

“What did those eight customers describe?” Sam asked.

James thought back to the calls. The frustration in their voices. “They could see everything happening in their business. Dashboards, reports, real-time data. But when an opportunity appeared—a market shift, a competitive opening, a customer signal—they couldn’t move fast enough. By the time they’d aligned everyone and made a decision, the window had closed.”

“So what do they actually need?”

“They need...” James worked through it. “Fast decisions? No, those can be wrong. Good decisions? No, those can be slow. They needed both. Quality and speed. But not all the time—that’s impossible. Exactly when it matters. When the window opens.”

James said it before he fully realized what he was saying: “Judgment at opportunity speed.”

The room went still. Not because it was clever. Because it was true.

“That’s the transformation,” James said. “That’s what becoming a high-velocity organization actually means. Having the judgment to act when the window opens.”

Sam wrote it on the board:

JUDGMENT AT OPPORTUNITY SPEED

The Engineering Director frowned. “But we still need something to show. Proof. Evidence.”

“What’s the proof?” Sam asked. “In Amalakai’s game, proof is a demo. Features working, screenshots, technical specs. In your game, what’s the proof?”

James felt something click. The same clarity he’d felt yesterday when the empty column revealed three years of drift.

“The proof is transformation,” he said. “Not that the tool works. That the transformation works.”

“Keep going.”

“If we can show Ramorian that we’ve transformed other organizations—that companies became high-velocity decision-makers using what we teach them—that’s proof Amalakai can’t match.”

The room shifted.

“Demo, then sell,” the Marketing VP said quietly.

“Demo transformation,” James clarified. “Prove we can help organizations become high-velocity. Then show Ramorian what we proved. Then build the enhanced platform alongside their implementation.”

Sam wrote on the board:

DEMO → SELL → BUILD

“That’s the sequence. You don’t build product first. You prove transformation first. Transform existing customers who already use Dayanos. Then sell that transformation to Ramorian. Then build the tools alongside them as you implement.”

“That’s backwards from how we always do it,” the Engineering Director said.

“Exactly,” Sam said. “Because how you always do it validates their category, not yours.”

“Wait,” the Product VP said. “Transform existing customers. You mean the eight James talked to weeks ago?”

James pulled up his notes. “Every one of them said the same thing in different words. They could see their operations better, but they couldn’t decide faster. They needed transformation, not tools.”

“So we go back to them,” the Marketing VP said slowly. “Offer transformation capability. Help them become high-velocity organizations. Document the results. That becomes proof for Ramorian.”

“Real transformation,” the Product VP added. “Not a demo. Before and after.”

Name The Game You’re Claiming

“But what do we call it?” the Product VP asked. “When we reach out to customers, when we pitch Ramorian—what’s the name for what we’re offering?”

The room went quiet. They had the concept. They understood the transformation. But they didn’t have language for it yet.

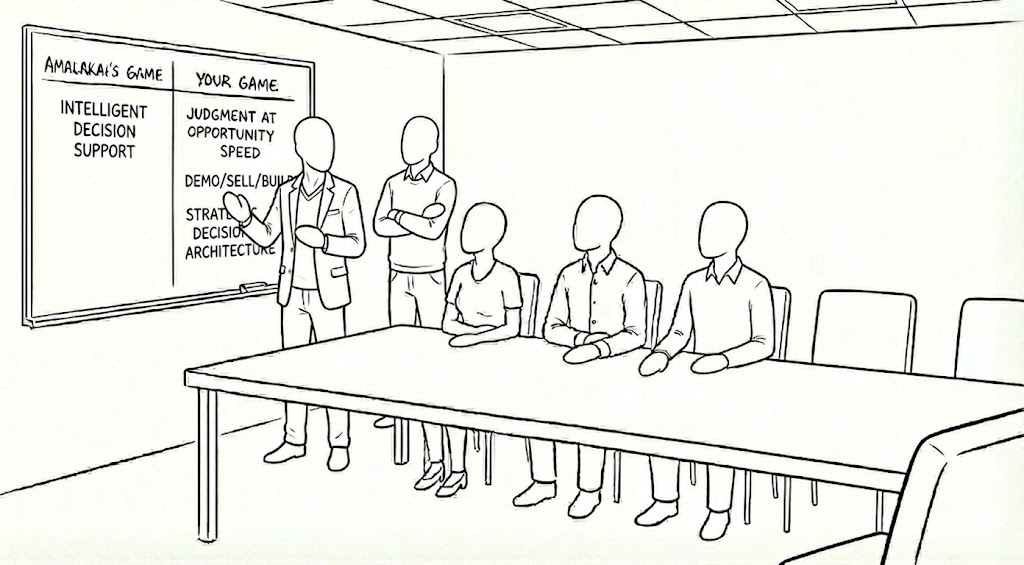

Sam moved to the whiteboard. “Let’s start with what already exists. What does Amalakai call what they do?”

The Product VP pulled up Amalakai’s website on his laptop. “Intelligent Decision Support. That’s their strategic positioning.”

Sam wrote it on the board:

INTELLIGENT DECISION SUPPORT

“Okay. So they own that language. That’s their territory.” Sam turned to face the team. “What’s different about what you’re offering? Not better—different. What are you doing that they’re not?”

“We’re not supporting decisions,” the Marketing VP said. “Support is reactive. You have a decision to make, here’s data to help. We’re doing something upstream of that.”

“What’s upstream?” Sam asked.

“Building the capability,” the Engineering Director said. “Teaching them how to architect their decision-making. So they don’t need support—they have the architecture.”

“Keep going.”

James thought about the flywheel and what they were actually teaching. “We’re not helping them with existing decisions. We’re teaching them how to structure strategic decisions so the right choices become obvious.”

“So it’s not support,” the Marketing VP said. “It’s architecture. The foundation that makes good decisions possible.”

Sam wrote below Amalakai’s positioning:

DECISION ARCHITECTURE

“That’s closer,” he said. “But which decisions?”

“Not all of them,” the Product VP said. “You can’t architect every daily decision. That’s overwhelming. We’re focused on the strategic ones—the decisions that determine whether they capture opportunities or watch them pass.”

“Strategic decisions,” the Marketing VP added. “Monthly, quarterly. The ones where judgment actually matters.”

Sam erased and rewrote:

STRATEGIC DECISION ARCHITECTURE

The room sat with it.

“That’s different from Amalakai,” the Engineering Director said slowly. “They’re downstream—supporting decisions that already exist. We’re upstream—architecting how strategic decisions get made in the first place.”

“And it’s not a tool,” James added. “It’s capability. Something they build. Something they become.”

“Can Amalakai claim this?” Sam asked.

“No,” the Product VP said. “They’d have to completely rebuild their offering to teach capability architecture.”

“And would they?” Sam pressed. “If this category takes off, could they pivot?”

The Engineering Director shook his head. “They’d lose their current revenue model. Software subscriptions based on tool usage. This is capability building—education, implementation, ongoing coaching. Different economics entirely.”

“So they’re locked in,” the Marketing VP said. “Even if they see us claiming this territory, their business model prevents them from following. They’re downstream by design.”

James wrote on the whiteboard below the positioning comparison:

AMALAKAI: Support existing decisions

DAYANOS: Architect decision capability

“That’s the distinction,” James said. “And Strategic Decision Architecture is what we’re teaching. The capability to have judgment at opportunity speed.”

“Wait,” the Product VP said. “If Strategic Decision Architecture is the capability we’re teaching, what’s Dayanos?”

The question hung.

Sam let them work through it.

“Dayanos is...” the Marketing VP started. “Dayanos is the platform. It’s what makes Strategic Decision Architecture scalable. You could technically implement the flywheel with any system—spreadsheets, documents, whatever. But Dayanos is designed for it. Built to support the architecture.”

“Like mobile computing and iPhone,” the Engineering Director said. “Mobile computing is the category. iPhone is the platform that delivers it best.”

“Exactly,” James said. “The architecture is the capability. Dayanos is the platform that makes it work at scale. System-agnostic in principle, optimized for Dayanos in practice.”

The Product VP leaned back. “So we’re not repositioning Dayanos. We’re creating a category that Dayanos enables.”

“And that means existing customers don’t lose anything,” the Marketing VP added. “They keep using Dayanos. But now we’re offering them Strategic Decision Architecture—the capability to transform into high-velocity organizations using the platform they already have. That’s changing the game entirely.”

“That’s the premium offer,” the Engineering Director said. “Not just the platform. Platform plus capability building.”

James saw the architecture clearly now. “Those eight customers already use Dayanos. We’re not selling them new software. We’re offering Strategic Decision Architecture—teaching them the three playbooks, installing the flywheel, building the capability. Dayanos becomes more valuable because now it’s supporting architecture, not just providing visibility.”

“And when we pitch Ramorian,” the Marketing VP said, “we’re not competing with Amalakai on decision support tools. We’re offering a different category entirely. Strategic Decision Architecture. The capability to become a high-velocity organization.”

“And Amalakai can’t follow us there,” the Engineering Director said. “They’re locked into decision support. We’re claiming decision architecture. Different territory entirely.”

Sam let that settle. “You just changed the question. Not ‘how do we compete faster’ but ‘what game are we playing.’ That’s the shift.”

The Marketing VP looked at the whiteboard. “We almost spent four weeks building a demo that would’ve validated Amalakai’s category.”

“Instead you spent three days finding territory they can’t claim,” Sam said. “That’s the difference.”

“Okay.” The Product VP opened a fresh page in his notebook. “We’re implementing this with existing customers. What does that actually look like? How long do we need?”

The question hung. James looked at the timeline on the whiteboard. Documentation and Ramorian pitch prep would take at least a week.

“We have about six weeks for active implementation,” James said. “Maybe less if we need buffer.”

“So we can’t afford a long installation,” the Marketing VP said. “Whatever we do, it has to work in three to four weeks.”

The Product VP frowned. “Can you transform an organization in three weeks?”

“You can’t transform them completely,” James said. “But you can install the capability. Prove direction. Show decision velocity increasing, coordination overhead decreasing. That’s enough proof for Ramorian.”

“But how?” the Engineering Director asked. “What do we actually do week by week?”

Sam had been quiet. Now he moved to the whiteboard. “The flywheel has five elements. But for installation, think of it as three integrated playbooks.”

He drew three circles:

PEOPLE MOBILIZATION

PRIME POSITIONING

OPERATING MODEL

“People Mobilization—understanding who you’re transforming and what that transformation looks like. Prime Positioning—articulating the territory you own. Operating Model encompasses the rest—how you architect work, what you prioritize, how you measure.”

“So we’re not teaching five separate things,” the Marketing VP said. “We’re installing three integrated playbooks.”

“And once they’re installed?” the Product VP asked.

“Then the flywheel becomes their operating rhythm,” Sam said. “Not something they practice. Something they use to coordinate decisions every week.”

James saw it. “So there are two contexts. Installation context—where we’re teaching the playbooks. Operating rhythm context—where they’re using the flywheel to coordinate their actual work.”

“Exactly,” Sam said. “You install over three to four weeks. Two turns through the flywheel. Then it travels with them—becomes the document in their meetings, the framework for their decisions. Not a strategy exercise. Their actual coordination architecture.”

“And after four weeks?” the Marketing VP asked.

“Week five, we document,” James said. “Decision velocity before and after. Coordination overhead trends. Time from insight to action. Real transformation metrics. Then we have two weeks to prepare the Ramorian pitch.”

“Tight,” the Product VP said.

“But possible,” James countered. “If we transform one customer in four weeks, we’ll have proof. If they’re measurably moving toward high-velocity organization, that’s enough for Ramorian.”

The Marketing VP pulled up her customer notes. “So which customer do we start with?”

James had been thinking about this since yesterday. “Kedaris. Their VP of Operations told me a week ago: ‘We love seeing what’s happening. We just can’t decide what to do about it fast enough.’ That’s exactly the problem Strategic Decision Architecture solves.”

“And they already trust us,” the Product VP noted. “We’re not building a relationship from zero. We’re offering capability to an existing customer who already uses the platform.”

“It’s offering what they actually need,” James said. “They told us a week ago. We just didn’t know what to call it yet.”

The Marketing VP was already drafting. “So we reach out to Kedaris today. Offer Strategic Decision Architecture as beta access. Four-week implementation. We’ll teach them the three playbooks, install the flywheel, help them become a high-velocity organization. Measure everything.”

“And if it works?” the Engineering Director asked.

“Then we have proof,” James said. “Real transformation. Real results. That’s what we show Ramorian. Not that Dayanos has better features. That Strategic Decision Architecture creates high-velocity organizations.”

Sam stepped back from the whiteboard. “Notice what just happened. You found the path that doesn’t require rebuilding product, abandoning existing customers, or competing on Amalakai’s terms. You’re leveraging what you have to prove what you’re claiming.”

The team looked at each other. The constraint that had felt impossible an hour ago—prove transformation before Ramorian signs with Amalakai—suddenly had a path.

“Kedaris first,” James said. “Four weeks to prove the method. Document results. Then we pitch Ramorian with real case studies—decision velocity doubled, coordination overhead cut in half, whatever the actual numbers show.”

“That’s what beats Amalakai,” the Product VP said quietly. “They can show Ramorian software. We’ll show them transformed organizations.”

Your First Move Sets The Rhythm

The team filtered out, energy different than when they’d arrived. Not anxious. Focused. The Engineering Director was already texting his team about clearing the next four weeks. The Marketing VP was drafting the Kedaris outreach. The Product VP reviewing customer data to sequence the other seven after Kedaris proved the method.

James was gathering his notes when Sarah appeared in the doorway. The board member watching his performance most closely over the past six months.

“Heard about Amalakai,” she said. No preamble.

“News travels fast.”

“Exclusive partnership with Ramorian.” She stepped into the room, scanning the whiteboard. “That was supposed to be our account.”

“It still can be.”

Sarah studied the whiteboard. The three playbooks. The four-week timeline. Demo → Sell → Build. And Strategic Decision Architecture written large across the top.

“Walk me through it,” she said.

James moved to the whiteboard. “We’re not rebuilding the platform. We’re proving transformation first. The capability to act when windows open. We implement it with existing customers over four weeks. Document results. Use that proof to win back Ramorian.”

“Four weeks to transform a customer?”

“Four weeks to install the capability and prove direction. Decision velocity increasing, coordination overhead decreasing. Measurable movement toward being a high-velocity organization.”

“Not much buffer,” Sarah said.

“No. But it’s the path that doesn’t require rebuilding product, abandoning existing customers, or competing on Amalakai’s terms.”

Sarah crossed her arms. “And if Kedaris doesn’t transform? If four weeks isn’t enough to prove this works?”

James met her eyes. “Then I walk into that board meeting without Ramorian, without proof, and you already know what happens next.”

Sarah held his gaze. The room was very quiet.

“You’re betting the company on this,” she said.

“I’m betting we can claim territory Amalakai can’t touch. If I’m wrong—” He gestured to the whiteboard. “At least we’ll know why before the board meeting. Not months later when it’s too late to course-correct.”

Sarah turned back to the whiteboard. Studied the structure. The operating rhythm design. The distinction between installation and coordination. Strategic Decision Architecture as category, Dayanos as platform.

“This is different from the last six months,” she said finally. “That was execution theater. Moving fast, building features, hoping speed would solve the strategy problem. This actually looks like strategy.”

“It is strategy.”

“But James—four weeks is aggressive. You’re compressing what usually takes quarters into twenty-eight days.”

“We’re not transforming them completely. We’re teaching the capability and operating rhythm. They continue transforming after we leave. We just need proof the direction is right.”

“We’ll measure Decision velocity, coordination overhead, time from insight to action. Those numbers will move in four weeks if the method works.”

Sarah was quiet for a moment. “And if Kedaris says no?”

“Then we go to the next customer. But I don’t think they’ll say no. They told us exactly what they needed weeks ago. This is the answer they’ve been looking for.”

“You sound clear about this.”

“I am. I know what we’re building. I know why it’s different from Amalakai. I know how to prove it works.” James paused. “Whether it works is the question. But the path is clear.”

Sarah studied him. James could see her evaluating. Not just the plan. Him. Whether he’d actually learned something from the last six months.

“Fifty-one days,” she said finally.

“You know what’s ahead if this doesn’t work.”

“I do.”

Sarah nodded once. Started to leave. Then turned back at the door.

“If you pull this off... you’ll have done something rare.”

She paused. “Good luck, James.”

James stood alone in the war room. The whiteboard showed everything they’d built over three days:

JUDGMENT AT OPPORTUNITY SPEED

STRATEGIC DECISION ARCHITECTURE

DEMO → SELL → BUILD

Four-week installation. Operating rhythm that persists.

And 51 days to prove all of it.

He pulled out his phone. Found the VP of Operations at Kedaris in his contacts. The call from a week ago where she’d said exactly what they needed: “We love seeing what’s happening. We just can’t decide what to do about it fast enough.”

James typed a message:

“Lisa - Quick question. You mentioned a week ago wanting to decide faster, not just see better. We’ve built something that might solve exactly that. Capability building for high-velocity decision-making. Four-week beta starting next week. Interested in a call tomorrow to discuss?”

He read it twice. Then hit send.

Three minutes later, his phone buzzed.

“Very interested. 2pm tomorrow work?”

James typed back: “Perfect. Talk then.”

He looked at the whiteboard one more time. Four weeks with Kedaris proving the method. One week documenting results. Two weeks winning Ramorian. Or walking into the board meeting knowing exactly why the company was about to change CEOs.

The Lightning Strike had begun.

PRACTICE: What Game Are You Playing?

Time: 5 minutes

Most strategy statements could be copy-pasted into any competitor’s deck. That’s how you know you’re renting their territory, not owning yours.

Try this right now: List your top three strategic priorities for next quarter.

Then ask: Could a competitor deliver this exact transformation?

If yes, you’re renting their strategy, not owning territory.

Examples that sound strategic but aren’t owned:

“AI-powered platform”

“Enterprise expansion”

“Product stability and scale”

These aren’t wrong. They’re just not yours.

Ownership sounds different:

“Helping customers make strategic decisions at opportunity speed”

“Teaching organizations to architect transformation capability”

“Building judgment systems that work at market velocity”

That’s transformation. That’s territory. That’s yours to own.

The game you choose determines how you move. Make sure you’re choosing your game.

Example from James’s team:

Almost said: “Build intelligent decision support faster than Amalakai.” → That’s Amalakai’s priority. Not theirs.

Actually claimed: “Teach Strategic Decision Architecture that transforms organizations into high-velocity decision-makers.” → That’s territory Amalakai can’t claim.

AI Prompt:

Here are my top three strategic priorities:

[Your priority]

[Your priority]

[Your priority]

Now test them: Could a competitor claim these exact same priorities?

If yes to any of them, help me:

1. Identify what I’m actually building that’s different - not better features, but different territory (transformation, capability, outcome a competitor can’t claim)

2. Rewrite those priorities as transformation statements - what customers become, not what we build

3. Show me the difference between rented positioning (competing on their terms) and owned territory (claiming ground they can’t follow)

4. Based on owned territory, what’s my first move that competitors fundamentally cannot copy?

Help me see the difference between strategic-sounding priorities and actual territory ownership.

Next Episode: Alignment Is A Contact Sport (Now Live)

James claimed Strategic Decision Architecture as territory Amalakai cannot follow. He designed a four-week method to prove it. Now the theory meets reality—51 days to transform a customer, document proof, and win Ramorian back. The Lightning Strike is underway.

Subscribe to follow James’s transformation journey, and share with a leader who’s tired of competing on someone else’s terms.

Regarding this, understanding game parametres is key, brilliant.