Traction at Opportunity Speed: Why Transformation ownership Beats Trend-Driven Innovation

How Heineken won by rejecting AI Friends

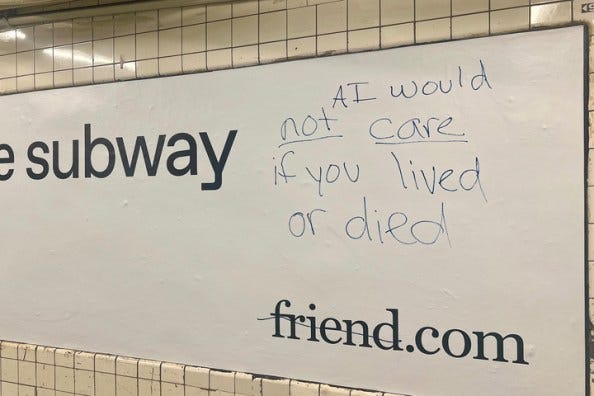

October 2025. New York City subway. Somewhere between the screeching brakes and the stale platform air, an AI startup’s million-dollar marketing campaign was getting a hostile rewrite.

“AI is not your friend.”

“Surveillance capitalism.”

“Get real friends.”

The graffiti sprawled across gleaming white advertisements for Friend—a $129 AI pendant that promised to be your “closest confidant.” The company had blanketed the subway system with 11,000 ads, one of the largest campaigns in MTA history. Within days, riders turned the posters into protest art.

Then something revealing happened.

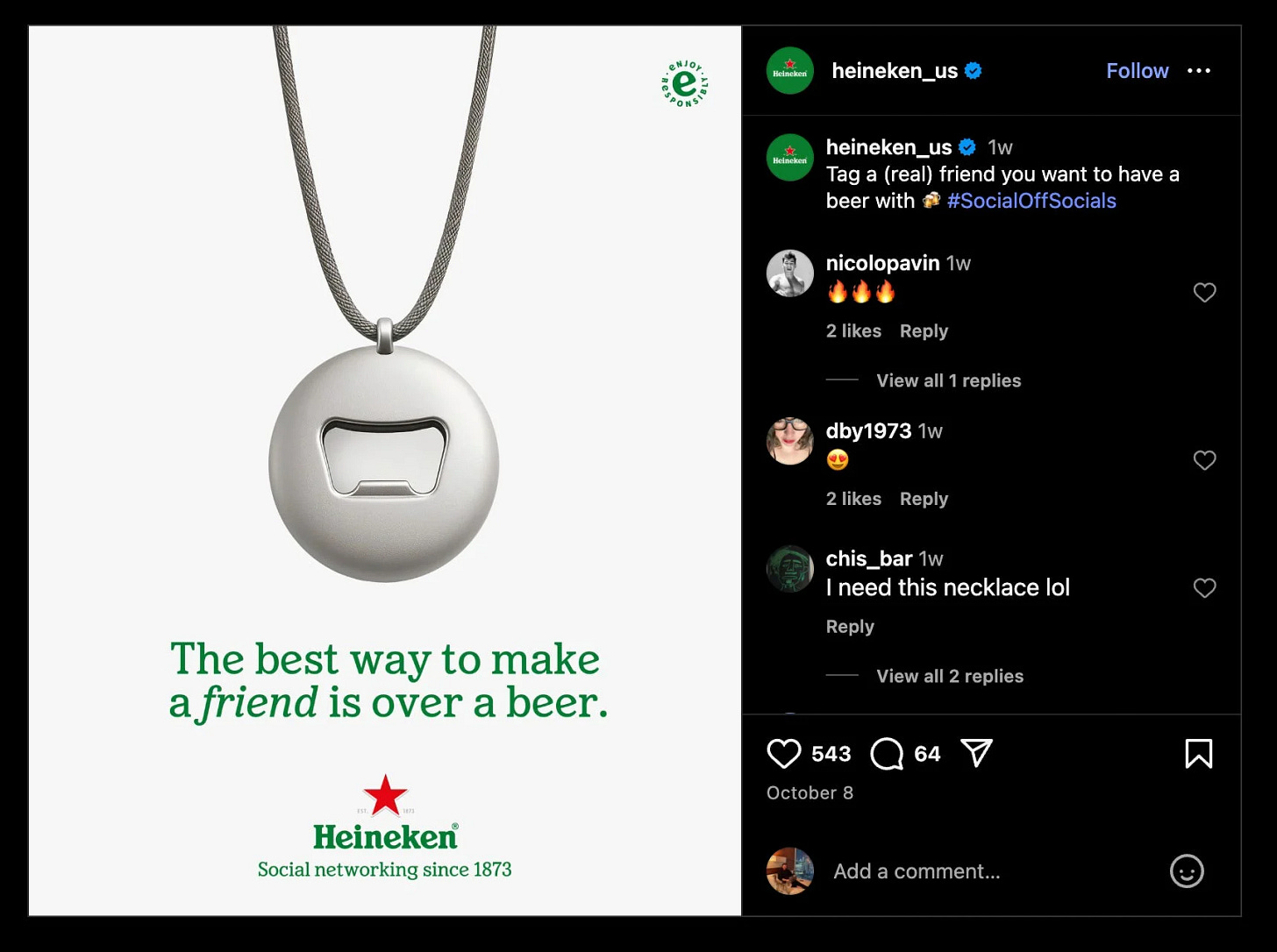

Two weeks later, Heineken launched their own campaign in the same subway system. Same format. Same audience. Different message: “The best way to make a friend is over a beer.”

Where Friend’s pendant appeared in their ads, Heineken showed a bottle opener necklace—their tongue-in-cheek “wearable tech.” The tagline underneath: “Heineken: Social networking since 1873.”

Friend’s 22-year-old CEO claimed the vandalism was “artistically validating” and part of his plan. Heineken said nothing about Friend directly. They didn’t need to. The graffiti had already written their market research.

Friend burned $1 million proving that people desperately want authentic human connection and viscerally reject digital substitutes.

Heineken built traction at opportunity speed, spending roughly $50,000 claiming the territory Friend’s failure had just validated.

The difference? Heineken owns the customer transformation story Friend was trying to automate. When you own transformation territory, you don’t react to trends—you recognize which trends validate what you already sell. And you move with precision while competitors are still explaining why their backlash was “part of the plan.”

This is how Prime Positioning works. And it’s why understanding customer transformation matters more than chasing technology trends.

Let me show you what actually happened here.

“Social networking since 1873.”

Four words revealed why Heineken could respond to Friend’s collapse with such precision.

Look at what that tagline actually claims. Facebook launched in 2004. Twitter in 2006. We’ve spent two decades calling these platforms “social networks” as if digital connection invented the category. Heineken’s response was a quiet correction: We’ve been doing this for 150 years. You just forgot what the words meant.

This is language reclamation—taking back territory that got borrowed so gradually nobody noticed the theft.

Think about what happened to “social networking.” The phrase originally described what humans do when they gather: share stories, build trust, create belonging. Then digital platforms appropriated the language, applied it to feeds and followers and algorithmic timelines, and convinced an entire generation that scrolling through content was the same as building relationships.

It wasn’t. It was a substitute. A convenient, scalable substitute—but a substitute nonetheless.

Heineken’s tagline exposes this. Beer has facilitated human connection since before electricity. The pub, the bar, the backyard gathering—these were the original social networks. Places where people brought themselves to the table, exchanged stories, and left transformed by the interaction.

Facebook’s “social networking” is renting space in Heineken’s prime territory.

This matters because language shapes category ownership. When you control the words, you control how people understand the territory. Friend AI tried to own “friendship” by naming their product after the end state. Heineken didn’t claim friendship—they claimed the facilitation of it. The infrastructure. The 150-year track record.

One approach signals desperation. The other signals authority.

Here’s the strategic pattern: Friend competed for attention in the “AI companionship” category—a category that didn’t exist six months earlier and may not exist six months from now. Heineken didn’t compete in any category. They reminded the market they invented the category everyone else was trying to digitize.

That’s the difference between chasing trends and owning transformation. Friend saw AI capability and asked “what can we build?” Heineken saw AI capability and asked “what does this validate about what we already do?”

The answer was written in spray paint across the New York subway system.

Why “Friend AI” Was Actually An Enemy

But language reclamation alone doesn’t explain why Friend failed so viscerally. The graffiti wasn’t just rejecting AI—it was rejecting something more fundamental.

“AI doesn’t care if you lived or died.”

That message appeared on multiple defaced posters. Read it again. This isn’t a complaint about technology. It’s a recognition of absent reciprocity. The subway riders weren’t saying “this tech doesn’t work.” They were saying “this thing can’t care about me because caring requires exchange.”

Here’s the insight that explains everything: Real transformation requires reciprocal exchange. Both parties have to bring something to the interaction. Both parties have to leave changed.

Think about how friendships actually form. You share something vulnerable. The other person receives it, processes it, shares something back. You receive that, it changes how you see them, you go deeper. Back and forth. Reciprocal. An exchange where both people contribute and both people transform.

Now look at what Friend AI offered: You talk at a pendant. The pendant texts back. There’s no exchange because the pendant has no self to bring. It has responses, not reciprocity. Processing, not presence. You pour in; it outputs. That’s consumption, not connection.

The graffiti artists understood this instinctively. When they wrote “AI doesn’t care if you live or die,” they were articulating the exchange principle without having language for it. A friend cares because caring is part of the exchange—I invest in you, you invest in me, we’re both changed by the investment. Remove the exchange, and you don’t have friendship. You have a service.

Friend AI named their product after the end state of a journey they couldn’t facilitate. That’s like calling a dating app “Marriage”. You don’t get to claim the destination when you can’t provide the path.

Heineken understood the path.

“Let’s grab a beer” isn’t about the beer. It’s a social contract. An invitation that says: I’ll bring myself to this interaction if you bring yourself. The beer is the excuse, the lubricant, the permission structure. But the transformation happens human-to-human, through exchange.

Here’s a useful test: Can you remove the product and still have the transformation?

Remove the Friend pendant, and there’s no interaction at all. The device IS the relationship. That’s replacement, not facilitation.

Remove the Heineken, and two people can still have a conversation. The beer made it easier, created context, lowered barriers—but the connection exists independent of the product. That’s facilitation, not replacement.

This is why Claude and ChatGPT feel different from Friend AI, even though they’re all “AI companions” in some sense. When you use Claude, there’s an exchange pattern. You contribute thinking. Claude contributes thinking back. It mirrors the reciprocal structure even if it’s not identical to human exchange. You bring a problem; you leave with new understanding. There’s a transformation arc.

Friend AI tried to replace human exchange entirely. It positioned itself as the friend, not the facilitator of friendship. And humans—even ones who couldn’t articulate why—recognized the absence immediately.

The pendant listened but couldn’t hear. It responded but couldn’t care. It was always on but never present.

That’s not a technology problem. That’s a transformation problem. Friend built a product without understanding the journey their customers actually needed to take. They saw “lonely people want connection” and jumped straight to “let’s provide connection” without asking “what does connection actually require?”

Heineken has been answering that question for 150 years. Connection requires showing up. It requires the other person showing up. It requires exchange—real, reciprocal, transformative exchange.

A bottle opener necklace can’t provide that. Neither can an AI pendant. But one of them knows it’s just a catalyst for what humans do together. The other thought it could be the replacement.

The subway riders knew the difference. And they wrote it on the walls.

How Heineken Built Traction at Opportunity Speed

The exchange principle explains why Friend failed. But it doesn’t fully explain Heineken’s response. Lots of companies could have seen the backlash and thought “we should do something.” Very few could have executed in two weeks.

Here’s the timeline:

September 25: Friend launches their subway campaign.

October 6-7: Backlash peaks. Graffiti goes viral. Media coverage explodes.

October 8: Heineken posts on Instagram—bottle opener necklace, “The best way to make a friend is over a beer.”

October 16-22: Heineken’s OOH campaign rolls out across the same NYC subway system.

Two weeks from cultural moment to full campaign deployment. In the same subway. To the same audience. With creative that directly referenced what Friend had just proven.

This isn’t normal. Most companies would still be in meetings debating whether to respond.

So what enabled Heineken to move this fast?

The answer is transformation clarity. When you own the customer transformation story, you don’t have to figure out what to say—you already know. The only question is whether the moment is right to say it.

Heineken has been running their #SocialOffSocials platform since April 2025.

This wasn’t their first execution. It was their fourth. Before Friend’s collapse, they’d already launched a mobile plan that rewards logging off, partnered with Joe Jonas on digital detox messaging, and created “The Boring Phone”—a deliberate throwback device for people tired of smartphones.

Friend’s backlash didn’t require Heineken to invent a new position. It required them to recognize that someone else had just validated their existing one. At scale. With a million dollars of someone else’s money.

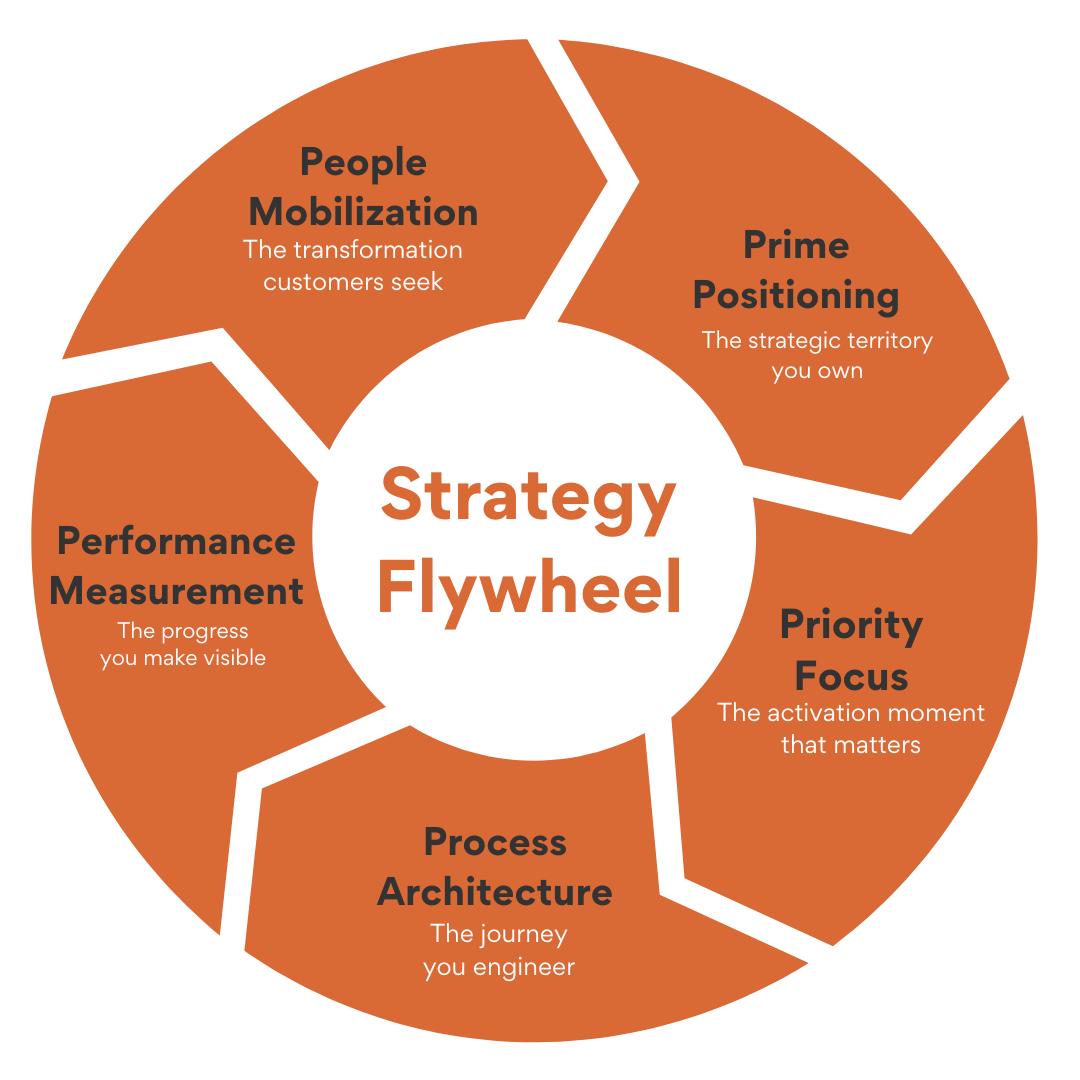

This is what transformation ownership enables: recognition speed.

When you’re clear on what transformation you facilitate, you can instantly sort incoming signals. Friend’s backlash wasn’t noise to filter out. It was signal that confirmed Heineken’s thesis—people want real connection, not digital substitutes. The graffiti wasn’t just protest art. It was a million-dollar focus group.

Recognition speed creates judgment speed.

Heineken didn’t need internal debates about positioning. They didn’t need to workshop messaging or test concepts. Their Strategy Flywheel was already turning. The #SocialOffSocials platform provided the template. The bottle opener necklace was a creative expression of territory they’d been building for months.

The decision wasn’t “should we respond?” It was “how quickly can we claim what they just validated?”

Judgement speed creates execution speed.

Same subway system. Same ad formats. Same audience that had just rejected Friend’s promise. Heineken borrowed their competitor’s distribution while that distribution was still culturally charged. The graffiti made Friend’s ads more visible, not less. Every defaced poster was a reminder that people wanted something Friend couldn’t provide—and Heineken could.

Their agency, LePub New York, had the creative infrastructure ready. The #SocialOffSocials hashtag was already established. The campaign didn’t require building from scratch. It required deploying what already existed into a moment that demanded it.

Execution speed creates value capture.

Friend spent over a million dollars creating awareness for a problem. Heineken spent roughly fifty thousand claiming the solution. The ROI differential isn’t about marketing efficiency—it’s about who owns the transformation territory when the moment arrives.

Friend created demand they couldn’t fulfill. Heineken fulfilled demand Friend had just created.

This is the compound effect of transformation clarity. Each speed component enables the next:

Recognition speed (see the signal) → Judgment speed (know the move) → Execution speed (deploy the system) → Value capture (claim the territory)

Remove any component and the chain breaks. Miss the recognition and you’re responding to old news. Hesitate on the decision and competitors fill the gap. Fumble the execution and the moment passes. Delay the value capture and someone else claims the territory.

Heineken hit all four because they’d already done the work. The transformation story was clear. The platform was built. The creative muscle was trained. Friend’s collapse was just the spark that lit fuel Heineken had been stockpiling.

Compare this to Friend’s timeline. Six months of product development. A million dollars in advertising. And when the backlash hit, what did they do? The CEO posed for photoshoots in front of defaced ads and told reporters the vandalism was “artistically validating.”

That’s not speed. That’s spin. It’s what happens when you don’t have transformation clarity—every crisis requires improvisation because there’s no foundation to build from.

Heineken didn’t improvise. They executed.

How Competitors Fund Your Strategy Campaign

Here’s the economic reality that most companies miss: When you don’t own transformation territory, your marketing budget awakens customers for your competitors.

Friend spent $1.8 million on their domain name. Over $1 million on subway ads. They burned through roughly 40% of their $7 million in funding on awareness—and what did that awareness create?

Three thousand units sold. Public protests. Graffiti that went viral. And a cultural moment that proved, at scale, that people desperately want authentic human connection and will reject cheap digital substitutes.

Friend created the demand. Heineken claimed it.

This is territory gobbling—the economic pattern where Prime Movers expand by harvesting customers that competitors awaken but can’t serve. It only works when you own the transformation story the competitor is failing to deliver.

Watch how the mechanism operates:

Friend’s campaign created massive awareness for a problem: loneliness, disconnection, the desire for companionship in an increasingly digital world. Real problem. Validated by their own research showing 72% of teens have used AI companions, with 30% using them for social interaction.

But Friend couldn’t solve the problem because they misunderstood its nature. They saw “people want connection” and built “device that simulates connection.” They skipped the transformation question entirely: What does real connection actually require?

Heineken had already answered that question. For 150 years.

So when Friend’s campaign validated the demand, Heineken didn’t see a competitor. They saw a $1 million investment in proving their thesis. The graffiti wasn’t attacking Heineken’s category—it was defending it. Every spray-painted message was a customer saying “I want what Heineken sells, not what Friend is offering.”

This is what transformation clarity enables. Heineken could instantly recognize that Friend wasn’t competing with them—Friend was validating them. The AI pendant wasn’t a threat to beer sales. It was proof that the market Friend was trying to create already belonged to someone else.

Technology-first companies miss this completely. They see capability and assume it creates category. Friend saw AI that could listen and respond, assumed that capability meant value, and never asked whether their solution addressed the actual transformation customers needed.

Transformation-first companies see it immediately. Heineken watched Friend’s launch, watched the backlash build, and recognized the pattern: Someone is spending a fortune proving that people want what we already provide. The only question was how fast they could claim the territory Friend had just illuminated.

Two weeks. Same subway. Fifty thousand dollars.

The territory expansion was immediate and permanent. Before Friend, Heineken owned “beer facilitates social connection.” After Friend, Heineken owns “authentic human connection versus digital substitutes.” They didn’t just defend their category—they expanded it by absorbing the counter-positioning Friend had accidentally created.

Here’s the strategic lesson: Friend’s failure wasn’t bad marketing. It was the inevitable result of building without transformation clarity.

When you don’t understand the journey your customers need to take, you can’t see when you’re validating someone else’s territory. You spend money creating awareness. You generate attention. You might even create cultural moments. But the customers you awaken go looking for solutions—and they find the company that actually owns the transformation you promised but couldn’t deliver.

Friend promised friendship. Heineken delivers the conditions where friendship forms.

One is a claim. The other is a capability.

The market knows the difference. And when it figures it out—often loudly, often publicly, often written in spray paint—the Prime Mover is there to welcome the awakened customers home.

Beer vs. AI is Isn’t The Real Story

It’s about what happens when transformation clarity meets cultural moment.

Friend had technology. Heineken had territory. When the moment arrived, territory won—not because beer is better than AI, but because Heineken knew exactly what transformation they enable and Friend didn’t.

That clarity is the asset. Everything else flows from it.

Recognition speed? You can only see signals when you know what you’re looking for. Heineken saw Friend’s backlash as validation because they already understood their transformation story. Friend saw their own backlash as “art” because they had no framework to interpret what the market was telling them.

Decision speed? You can only move without hesitation when the path is clear. Heineken’s response required no internal debate because their positioning wasn’t up for discussion. Friend’s CEO was still doing media interviews explaining why vandalism was actually good news.

Execution speed? You can only deploy fast when the system already exists. Heineken’s #SocialOffSocials platform was on its fourth execution. Friend was improvising crisis communications.

Value capture? You can only claim territory when you know it’s yours to claim. Heineken expanded from “social beer” to “antidote for digital loneliness” because they recognized the adjacent territory Friend had just validated. Friend watched their million-dollar awareness campaign become someone else’s market research.

Every speed component depends on transformation clarity. Remove it, and you’re just moving fast in random directions. Add it, and opportunity speed becomes a compound advantage that competitors can’t replicate—because they’d have to do the transformation work first.

Here’s the diagnostic question worth asking: If a competitor in an adjacent space failed publicly tomorrow, would you recognize it as validation of your territory? Or would you watch from the sidelines, unsure whether it had anything to do with you?

Heineken knew instantly. They moved in two weeks. They claimed the territory with fifty thousand dollars while Friend was still explaining why a million dollars in defaced ads was “artistically validating.”

That’s not luck. That’s not opportunism. That’s the compound advantage of knowing what transformation you own.

The AI era will produce more moments like this. Technology companies will launch products that promise transformation they can’t deliver. Some will fail quietly. Others will fail loudly, publicly, expensively—creating cultural moments that validate demand for solutions they can’t provide.

The companies that own transformation territory will recognize these moments for what they are: market research funded by someone else, awareness campaigns paid for by competitors, demand generation for solutions that already exist.

The companies without transformation clarity will watch it happen and wonder if they should “do something with AI.”

Friend spent a fortune proving that people want real human connection. The answer was never going to be a pendant that listens but can’t hear, responds but can’t care, promises friendship but can’t exchange.

The answer was always going to be something simpler. Something that’s worked for 150 years. Something that requires two people, a reason to gather, and the willingness to show up.

Heineken just reminded everyone they’ve been providing that answer since 1873.

The graffiti was the market talking. Heineken was the only one listening.

Strategy Flywheel™ Diagnostic: Competitor Failure Analysis

The analysis above emerged from running Friend AI and Heineken’s response through a systematic diagnostic framework. Below is the exact prompt structure that revealed these insights.

You can use this on any situation where a competitor fails publicly and creates potential territory for you to claim.

The Diagnostic Prompt

Copy this entire prompt and customize the [bracketed sections]: